Three Babies, Three Decades

This was a difficult post to write. I’m a mother of a 2 year old little girl, and it made my heart ache and my chest tight to think of losing her like so many Appalachian women lost their babies before me. It’s a difficult post to read. I’ve dispersed adorable historical photographs of West Virginia babies to make it a bit easier.

When I was pregnant with my daughter, I had a relatively uneventful pregnancy. I had more aches and pains than some, because of pelvic joint issues, but otherwise I did well. However, the first year of her life was stressful. She was born with her cord tightly wrapped around her neck and required 4 minutes of resuscitation. When she was about 9 weeks old, she went from being a playful infant to dehydrated with a high fever over the course of hours. I rushed her to the ER where she was discovered to have a severe urinary tract infection. One night when she was about 9 months old, she began having respiratory distress. I had a pulse oximeter at home and her oxygen level was 80% and dropping. Again we rushed her to the ER where she was diagnosed with a bad lung infection (RSV) and spent the next 2 days in the hospital, occasionally receiving supplemental oxygen. However, thanks to excellent medical care, she’s doing great now. She has no lingering issues from her birth or her RSV and is a wild, beautiful, joyful, happy, and fearless 2 year old.

My husband’s great-grandmother (who we called Mawmaw) was not so lucky. She made it safely through delivery of her children but lost two of her babies. During one pregnancy she caught the flu and became very ill, going into preterm labor. The baby was born too early for 1930s medicine to save. Another baby spiked a high fever when he was a couple months old. There was no medicine to give him and nothing to do. He had seizures in her arms all day, and then passed away.

Doing research for my thesis, I came across a coalfield doctor’s death certificate records. He kept hundreds of copies of death certificates for patients he had cared for. On one from 1950, he wrote “The child was brought hurridly into Huntington Memorial Hospital in a dying condition and lived approximately 10 or 20 minutes…Child was pulseless when I first examined it—rattling in the chest. Parents stated that the child was treated by some other physician for pneumonia.” The child in question was only 5 months old.

Mawmaw and I were both West Virginia women, having West Virginia babies, in West Virginia communities. However, I was able to greet pregnancy and childbirth with excitement and security, knowing that if something happened, I would be surrounded by doctors. The infant and maternal mortality rate in Appalachia is worryingly high compared to other industrialized regions. However, it has come a long way from the beginning of the 20th century. At the time the coalfield doctor above was writing his death certificates, and Mawmaw was grieving her babies, the infant mortality rate was very high. In some Appalachian counties, it was twice or more the national average. Today, the total infant mortality rate for West Virginia is 7.1 per 1000 live births. At the time of the Boone Report, which I discussed in my last post, the infant mortality rate in West Virginia was 53 compared to a national average of 39.8.

Infant mortality was a heartbreaking epidemic that visited many families in Appalachia. Like tuberculosis, it was an epidemic that wasn’t that long ago. Both my paternal and maternal grandmothers lost children. If you spend any time in Appalachia talking to grandmas and great-grandmas you will find most of them had the same experience.

So, what happened? Why did so many Appalachian babies die? They died for the same reason tuberculosis hit the area, and intestinal parasites and malnutrition were common: poverty and lack of access to good medical care. Of course, these issues are still present today. This is why Appalachians still have a higher-than-average rate of infant mortality as well as a higher rate of diseases linked to socioeconomic factors, such as diabetes. However, access to good medical care and improved infrastructure has progressed substantially since 1900, and this has saved babies’ lives.

The shift from pre-industrial to industrial

The term “infant mortality” includes babies who die just before or during birth, and after birth but younger than age 1. Babies who die just before or during birth are more likely to die secondary to problems with the mother, such as malnutrition. Babies who die after birth, especially during the time of highest infant mortality in Appalachia, were most likely to die from diseases. When Appalachia first opened up to industrialization at the end of the 1800s, medicine was very primitive. This was common in rural areas around the country. The huge leaps that medicine made during the 19th century were mainly confined to urban areas and were slow to trickle into rural areas, especially isolated rural areas such as Appalachia. There were doctors, but they were few and far between as well as expensive. Appalachians instead treated themselves using what we would call “folk remedies”: a combination of herbal and other treatments that were a combination of traditions from Europe as well as Native American medicines. Midwives delivered babies. Midwives can manage many births, but sometimes aggressive medical intervention is needed, and this was not possible in these communities.

As the region opened up, doctors with a more urban education moved in to the area. They displaced the doctors who had long-term relationships with Appalachian communities. The benefit of this was that modern medical techniques were brought into the communities which began improving their health status. The downside of this was that the relationship between Appalachians and their doctors fundamentally changed from that of close neighbors with informal payment arrangements to a much more formal, professional, and strictly fee-for-service basis.

Progressive Reform

At the same time that outside doctors began to come into the region, outside health reformers began to enter the region as well. These reformers tended to be young, middle or upper-class women from urban areas who were frustrated by their traditional roles and wanted a more varied life beyond being wives and mothers. They were members of the Progressive movement which was seen throughout the country in the first decades of the twentieth century. They were especially concerned with the health and wellbeing of pregnant women, infants, and children.

They established health education programs to reach out to Appalachian homes. One such program, the Frontier Nursing Service, established a successful visiting nurse and midwife service. This ensured that Appalachian mothers in their service area would have trained attendants at their deliveries. They would also visit homes to check up on infants and children. However, these programs clashed with local doctors. Many of them did not believe that anyone other than trained physicians could offer health education or obstetrical care, and they did not cooperate with these groups. As a result, while infant mortality improved during this time period it still lagged behind the rest of the country.

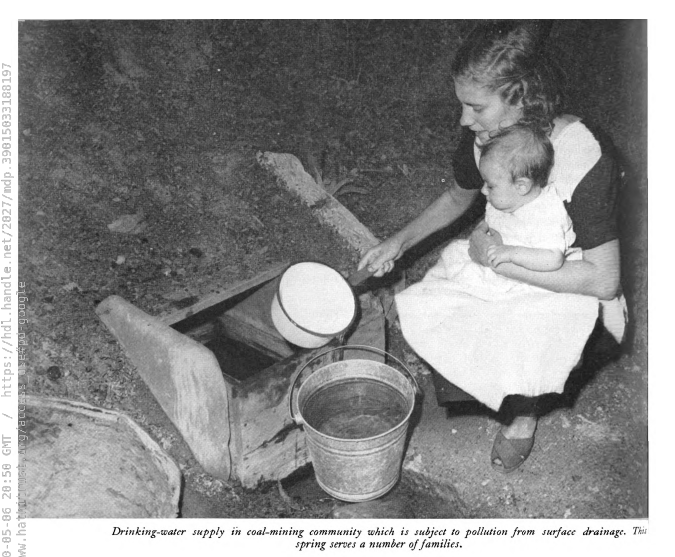

As with tuberculosis, the Boone Report was a significant turning point for infant mortality in Appalachia. The report contained tables of infant mortality rates, comparing rates in coalfield communities with the rest of the country. It was also filled with pictures of Appalachian homes, showing the many difficulties faced by mothers and children. Waste disposal was a problem and most coal camps didn’t have adequate sewage or garbage disposal. Houses were in poor repair with gaps in the walls and were bitterly cold in the winter. The vaccines we have today for our babies either didn’t exist or were hard to get, and babies died of illnesses that are easily preventable today.

The UMWA Health and Retirement Fund and the ARC

Also as with tuberculosis, the UMWA Health and Retirement Fund helped the region. It provided medical care to miners and their dependents and women were able to have contact with doctors. Their children could be cared for by doctors when they were sick. However, the two biggest things that helped improve infant mortality was the advent of numerous vaccines for babies and the growth of public health programs to administer them. Babies could be vaccinated and saved from meningitis, pneumonia, diphtheria, hepatitis, polio, and measles. The Appalachian Regional Commission made childhood vaccination a key feature of its health programs, drastically increasing the vaccine rates among children. This made an enormous difference in the infant mortality rate.

It is very important to note that throughout all of this, Appalachian women were not passive bystanders in their health and the health og their children. While many of the changes happened as a result of outside intervention, their success still depended on the cooperation of Appalachian families. They began rushing their sick babies to the doctor, and most importantly they agreed to have their babies and children vaccinated. As mothers have always done, they deeply cared about their children. Losing their baby was an unimaginable horror, regardless of how common it was, and they were willing to do whatever necessary to prevent it.

Appalachian Babies Today

Today, things are much better. West Virginia has one of the highest rates of childhood vaccination in the country, thanks to the good sense of its parents and strong vaccination laws. 2020 statistics showed that 98% of all kindergartners enter school with all CDC-recommended vaccines. As a result, our children are kept safe from deadly and disabling diseases. Our parents listen to the science of vaccines and as a result we have significantly decreased infant mortality.

There’s still work to be done. We still exceed the national average in infant mortality, and some of the reasons why haven’t changed. Poverty is still an issue and there is still a significant issue with access to prenatal care and good nutrition. West Virginia mothers tend to have more chronic health conditions than elsewhere, and this also affects their babies. However, we worked with health authorities to drop our infant mortality rate from 53 down to 7. We can certainly drop it further.

Further Reading

Melanie Beals Goan, Mary Breckinridge: The Frontier Nursing Service and Rural Health in Appalachia (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008)

Sandra Barney, Authorized to Heal: Gender, Class, and the Transformation of Medicine in Appalachia, 1880-1930, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000)

America’s Health Rankings website: https://www.americashealthrankings.org/