West Virginia is not only about coal. Our history cannot be simplified down to our relationship with only one industry. We have had many industries come and go over the years, for better or worse. Our identities do not come down to our relationship with this industry. However, to understand West Virginia today, it’s vitally important to understand the history of coal in Appalachia.

It is a much weaker economic force today than it was at its peak in the early twentieth century. However, coal continues to dominate much of the political discourse in West Virginia. Political careers can be ended by a politician’s stance on coal or his or her perceived stance on coal. Coal interests continue to have a significant presence in the hallways of the West Virginia state capitol building. Most West Virginians have not, in fact, been coal miners. However, the coal industry has had the largest influence on state development of any industry throughout the past one hundred years.

Early Beginnings

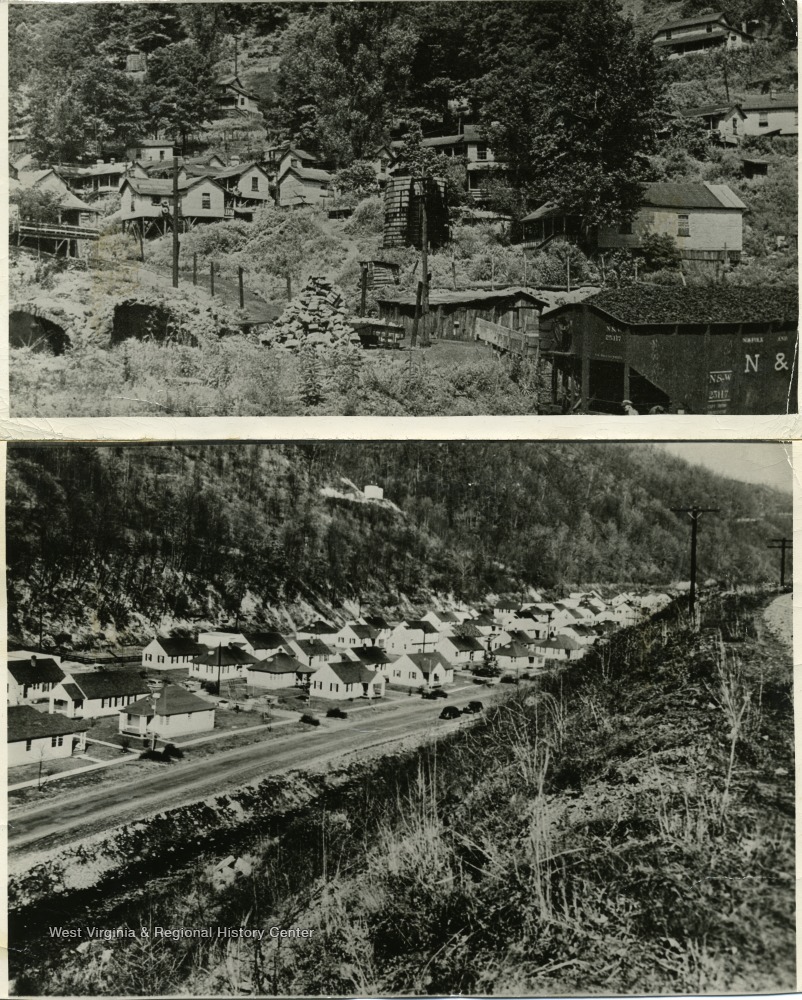

The first commercial coal mine was opened in West Virginia[1] in 1810, near Wheeling. West Virginia in 1810 was still very much frontier, with primitive infrastructure and few population centers. In 1883, the first major rail lines were completed, opening up the interior of West Virginia to the industrial centers of the East Coast. Carnegie’s mills were booming, homes were beginning to use coal more often as a source of fuel, and the steam engines that traversed the United States were fed with coal. Here, in the hills of West Virginia, lay a seemingly inexhaustible stockpile of desperately needed fuel.

The railroads made it possible for West Virginia coal to be easily exported to manufacturing centers. Industrialists poured into the isolated coalfield communities searching for coal. They did not let the presence of native West Virginians deter them. Prospective coal company owners secured the forces of large legal teams to obtain the deeds to vast tracts of West Virginia land, after which they evicted the inhabitants and began construction of mines. The inhabitants of the area, who were overwhelmingly farmers, now had no home and no livelihood. It was a catastrophic change to the future coalfields of West Virginia and it wreaked havoc on families and communities. Denise Giardina described it in her masterpiece, Storming Heaven:

“We lived in Winco, West Virginia, once our homeplace. American Coal Company owned our house. Richmond and Western Railroad owned our land. Mommy never talked about the old days, but Daddy told me how it used to be. Our cabin had set on the same piece of ground as the company store, which was three stories high, wood painted white with black trim, with stone steps trailing up to plate glass windows. ‘American Coal’ was painted in gold on the glass door. Daddy said the cabin used to creak when it was windy, but the company store stood firm and unyielding. The railroad track, its ties oozing tar, ran through Mommy’s vegetable garden. Most of the houses were built around the hill where the cow and sheep had grazed.”[2]

A Region is Colonized

The inhabitants of the coalfields had nowhere else to go, so they turned to the only major employer remaining in the area: the coal companies. It was at this point that coal sunk its claws deep into Appalachia. The miners endured incredibly dangerous working condition, risking life and limb underground and had little to show for it. The company owners portrayed themselves as benefactors to the outside world. They proclaimed the poverty of the coalfields and the necessity of the mines to provide desperately needed jobs.

The stereotype of the impoverished, illiterate “hillbilly” took hold in this period. It provided a useful justification for coal company owners to colonize the region. Missionaries from East Coast urban centers poured in to the region, hoping to educate and save a group of people who were no strangers to either education or Christianity. Coal company profits went to the pockets of the company owners—and the politicians and local law enforcement officers that they supported. The standard of living decreased. In most communities, the people were worse off after coal than before.

In response to this, the miners unionized. They fought. They held strikes. The Mine Wars came and went, and the United Mine Workers of America found power in the coalfields. However, coal, like all natural resources industries, is subject to boom and bust cycles. Periods of massive production and growth are quickly followed by long periods of unemployment and wage cuts. The coal industry is affected by international market factors and coal prices rise and fall with international markets. You cannot uncouple coal from manufacturing, transportation, and energy production. The first decades of the 20th century exemplify this well. World War I saw increases in coal outputs to help fuel war efforts. However, as industry crashed in the Great Depression the coal industry also collapsed. In the closing years of the 20th Century and the past nineteen years of the 21st Century, coal has been increasingly replaced by more efficient fuel sources.[3]

Coal in the 21st Century

Other states with economies dependent on natural resources buffer the bust cycles by taxing the companies during boom cycles. Alaska has done this very successfully with its oil industry, to the point that native Alaskans receive a check every year from the oil industry tax fund. West Virginia has failed throughout its relationship with coal to levy appropriate taxes against the industry. The boom cycles never benefited the state as they should have. State coffers were never filled as they should have been. When the bust cycles inevitably came the state’s economy plummeted.

While the UMWA was able to bargain for excellent wages and healthcare for its members, when the coal industry began to decline the coalfields began to decline with it. The stereotypes of Appalachian poverty became much more rooted in reality. The War on Poverty declared Appalachia in desperate need of federal intervention, much as missionaries and coal company owners had declared at the end of the 19th century. The coalfields continued to deteriorate, and today the people who remain there have to face massive health, economic, and social challenges to survive.

Now, West Virginia and much of Appalachia finds itself in the center of a battle over what the future of the United States should be. Is it looking forward, to a post-industrial economy, towards a minimum guaranteed income and a strengthened safety net? Or is it looking to the past, to a coal industry that never truly benefited West Virginians the way that it should? To capitalism and the free market, regardless of the human cost?

[1] Of course, “West Virginia” the state did not exist in 1810 and was simply “Virginia”. However, for purposes of this discussion any location within the present-day borders of West Virginia will be referred to as West Virginia.

[2] Denise Giardina wrote one of the finest pieces of West Virginian literature when she wrote Storming Heaven. It is a masterpiece and I recommend it to anyone who wants to understand the region and the era of the Mine Wars.

[3] The West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy has done extensive work documenting the rise and fall of the coal industry and its effects on the West Virginia economy. https://wvpolicy.org/

Very happy to see your blog Mollie, will be following it!!!

Very interesting. I love history and I hope to follow your blog. My father was a coal miner as well as my grandfather. I have lived in a little coal mining community most of my life. I still live in the company house that was purchased by my grandparents many years ago. Russell Bonasso wrote a book tilted Fire In The Hole detailing some of the mining communities in Marion County. It is an interesting read. Good luck Mollie.

I hope you enjoy the stories!