Memes of Resistance

Over the past couple weeks, I have seen a lot of posting on social media about the historical roots of Appalachian protesting. Specifically, the posts mention that to protest injustice is a key part of our Appalachian identity and heritage. The most common example that I see is that of the Mine Wars in southern West Virginia and the Battle of Blair Mountain, in which thousands of striking miners were fired upon by federal troops. The argument is that Appalachians, especially West Virginians, should see a sort of protest kinship with the Black Lives Matters protestors. We, too, have been exploited and killed and fought back and we need to do the same for others.

This argument seems simple and and meme-able, but has many more layers to it than Facebook would show. Miners have suffered at the hands of coal companies, but even in the mine wars there existed white privilege. White miners did not suffer in the way that African-American miners did. There is also the issue of lynching, which plagued the Appalachian coalfields like it has the rest of the country. Appalachian communities were also segregated communities. We certainly have our own history of racism with which to reckon and our own sins to amend.

There are other layers, however, such as the racial activism of the United Mine Workers of America. Many people think that the UMWA and the mine labor movement focused solely on issues such as pay and safety. The miners cared about so many more issues. One of these issues was a persistent demand at their conferences for the UMWA to condemn racism and discrimination. They also demanded that their leaders and politicians work to change Jim Crow laws across the country.

For my thesis, I have spent a lot of time reading over the past proceedings of the UMWA National Convention. I came across civil rights resolutions and demands time and time again. Ultimately, these resolutions did not rapidly change the lives of African-Americans (and may be examples of performative allyship). However, they do underscore the fact that the most radical of Appalachian resistance has included anti-racism. If you’re going to claim Sid Hatfield and Matewan as part of your cultural heritage, you also need to claim the anti-racism of the miners. It is as Appalachian to condemn police brutality against BIPOC as it is to demand that coal companies honor their pension plans.

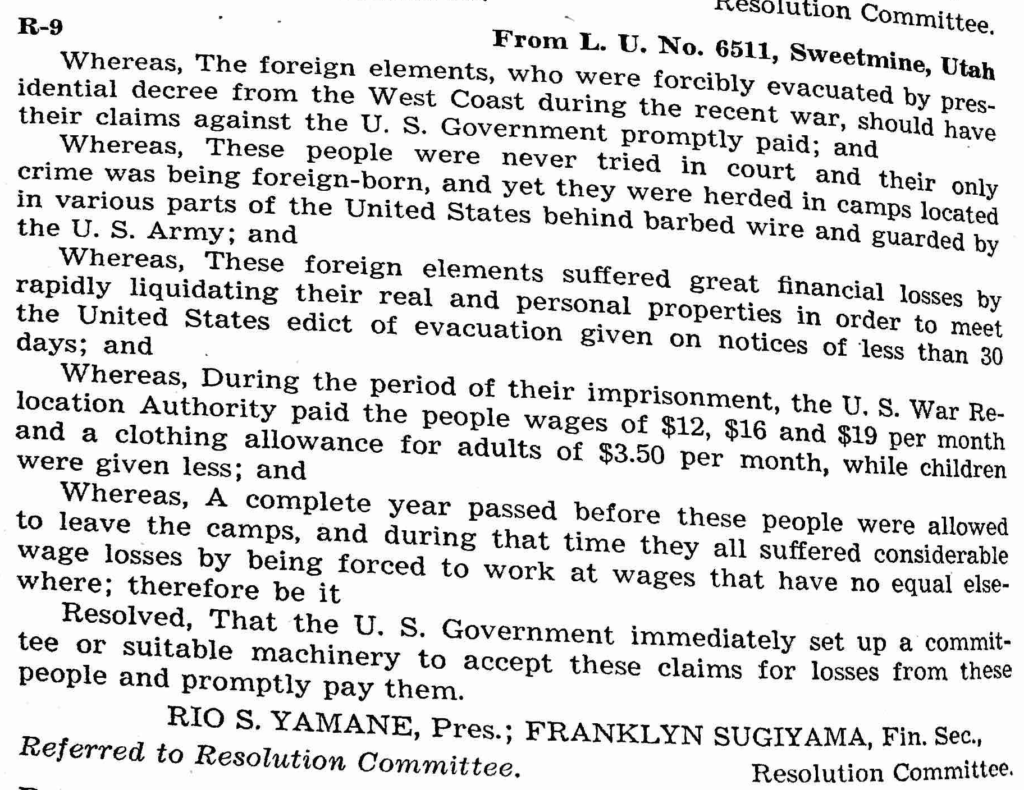

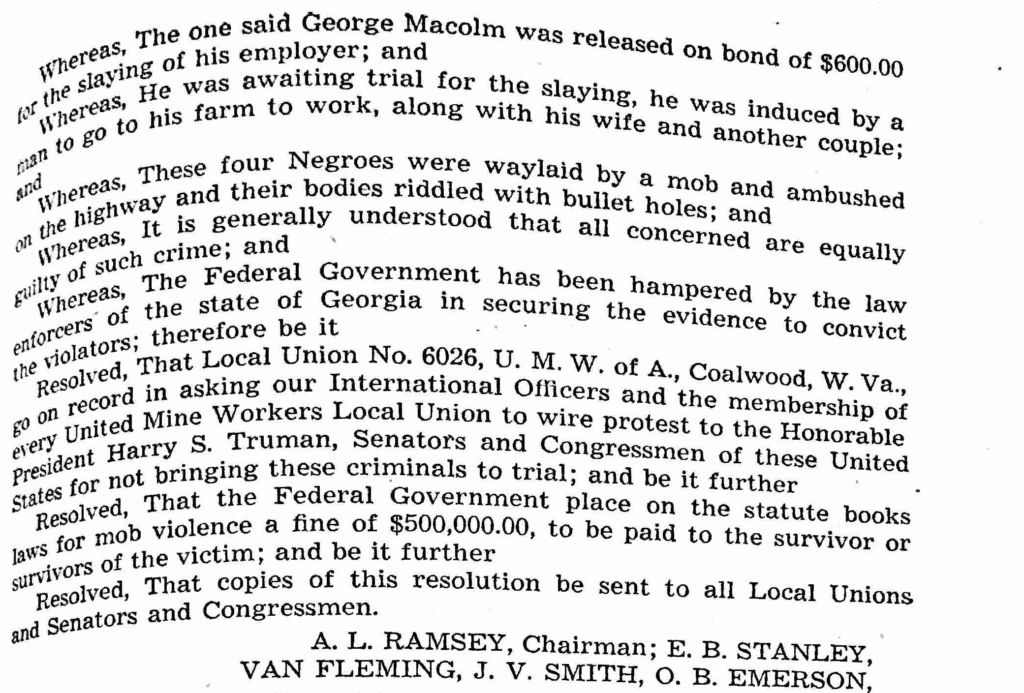

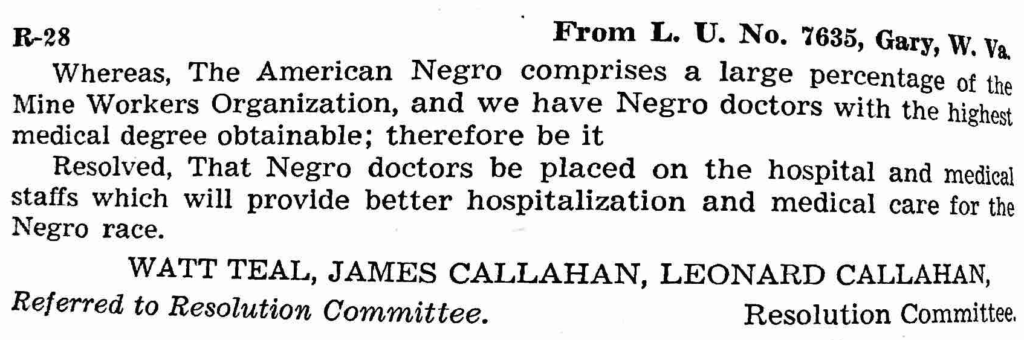

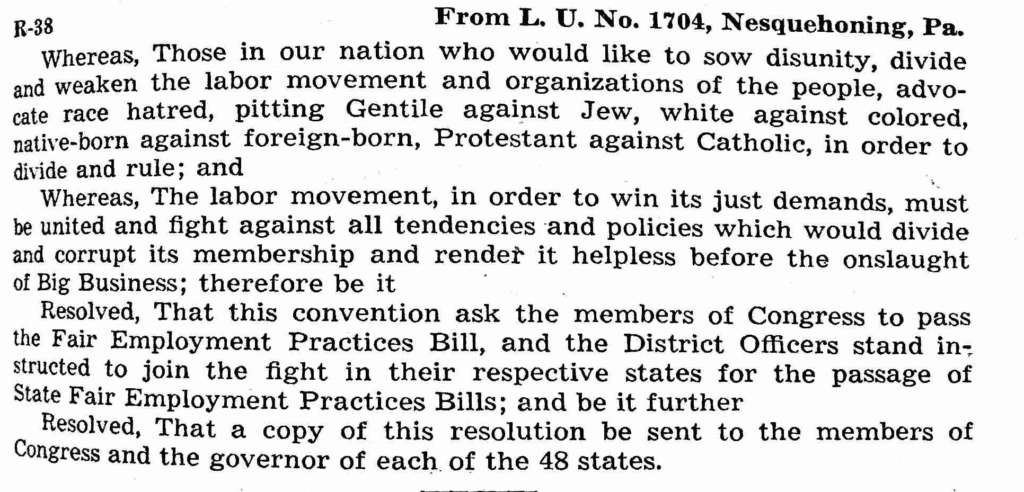

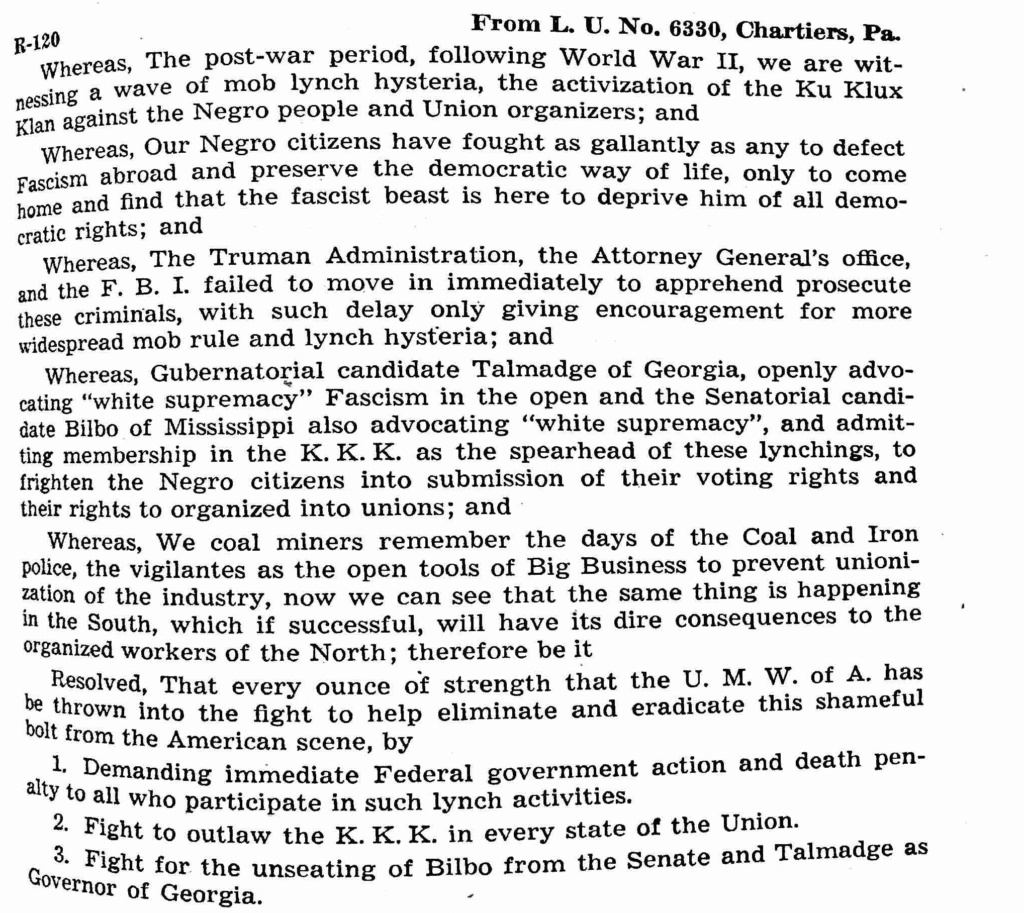

So, without further ado, I am going to share some of these resolutions to illustrate just how prevalent UMWA anti-racism was. I have seen such resolutions throughout at least twenty years of UMWA conventions. For the purposes of bandwith (and brevity), I am going to share the strongest ones from the 1946 convention.

Anti-Racist Resolutions

This last resolution, with particular eloquence, lays out the reasons why racial issues affect all Americans. Racism is a tool of despots, used to turn groups against each other. A divided populace is a populace that is easier to control. By creating narratives in which injustice can find rationale it is easier to continue to oppress others. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. put it: Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice anywhere.