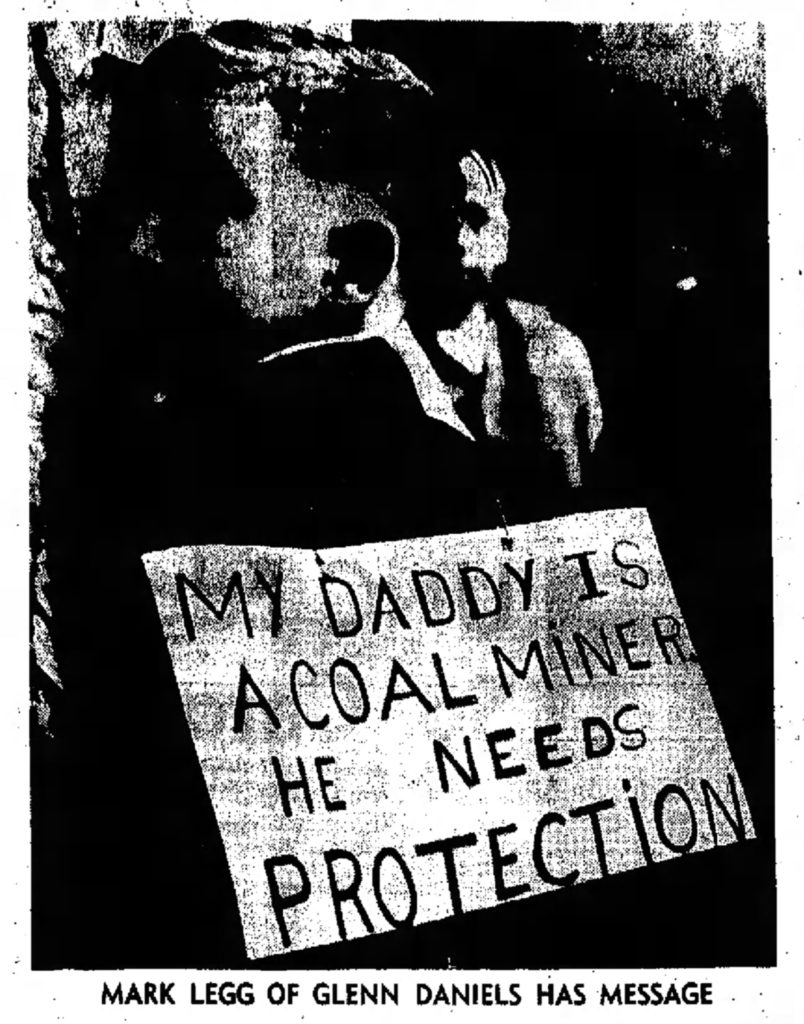

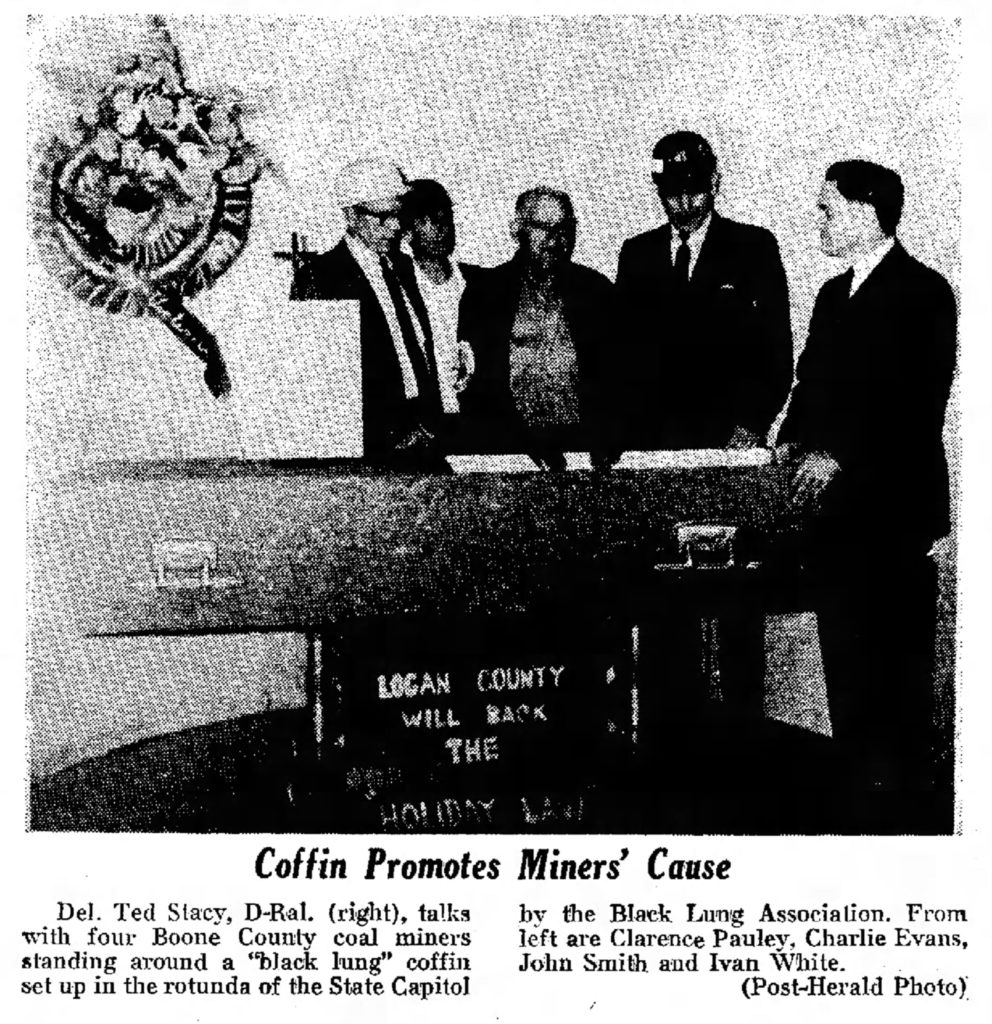

On this day in 1969, 2000 miners marched on the West Virginia State Capitol to demand recognition of black lung disease. Eight days before, on February 18th, the mines in the southern West Virginia coalfields emptied as miners walked off the job. This “wildcat” strike was not authorized or endorsed by the miners’ union, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). However, in the months leading up to these events, a growing number of West Virginia miners had grown dissatisfied with UMWA leadership. Seeing corruption in the leadership and feeling their concerns about their health were being ignored, an internal movement to oust corrupt UMWA leadership had formed. An additional movement, the Black Lung Association, formed to focus on recognition of black lung disease.

In 1969, black lung disease was not officially recognized as an actual medical condition and was not recognized as a disease eligible for workman’s compensation benefits. These benefits were only awarded to miners meeting the criteria for a specific list of illnesses. Since black lung was not recognized as even existing in the West Virginia coalfields, the countless men who were battling this terrible disease were unable to receive benefits. Instead, they were subjecting their lungs to further damage in the mines or living off of the charity of their communities and their UMWA local chapters to make ends meet. The United States lagged far behind in their recognition of this disease. Great Britain, for instance, had listed it as an official work-related illness in 1943.

By February 26, 1969, the miners were fed up. They were fed up with their union, fed up with the coal companies, and fed up with a state government that seemed to privilege the companies over the lives of its citizens. This mass strike was dramatic and effective, and the rally in Charleston brought it to the front door of the state government. Miners shared stories of themselves and their loved ones slowly suffocating as their lungs filled with coal dust and scar tissue. Widows demanded compensation after watching their husbands waste away. Physicians took the podium and described, in explicit detail, how coal dust was damaging the lungs of miners and how it would kill many of them unless immediate action was taken by the government and the companies.

The pressure worked. A bill was rapidly introduced into the House regarding the disease, but it was blasted by the miners as being insufficient. The state’s remaining coal miners left work, and by March there was not a single miner at work. Finally, on March 11, 1969, Governor Arch Moore signed a version of the bill meeting the miners’ demands into law.