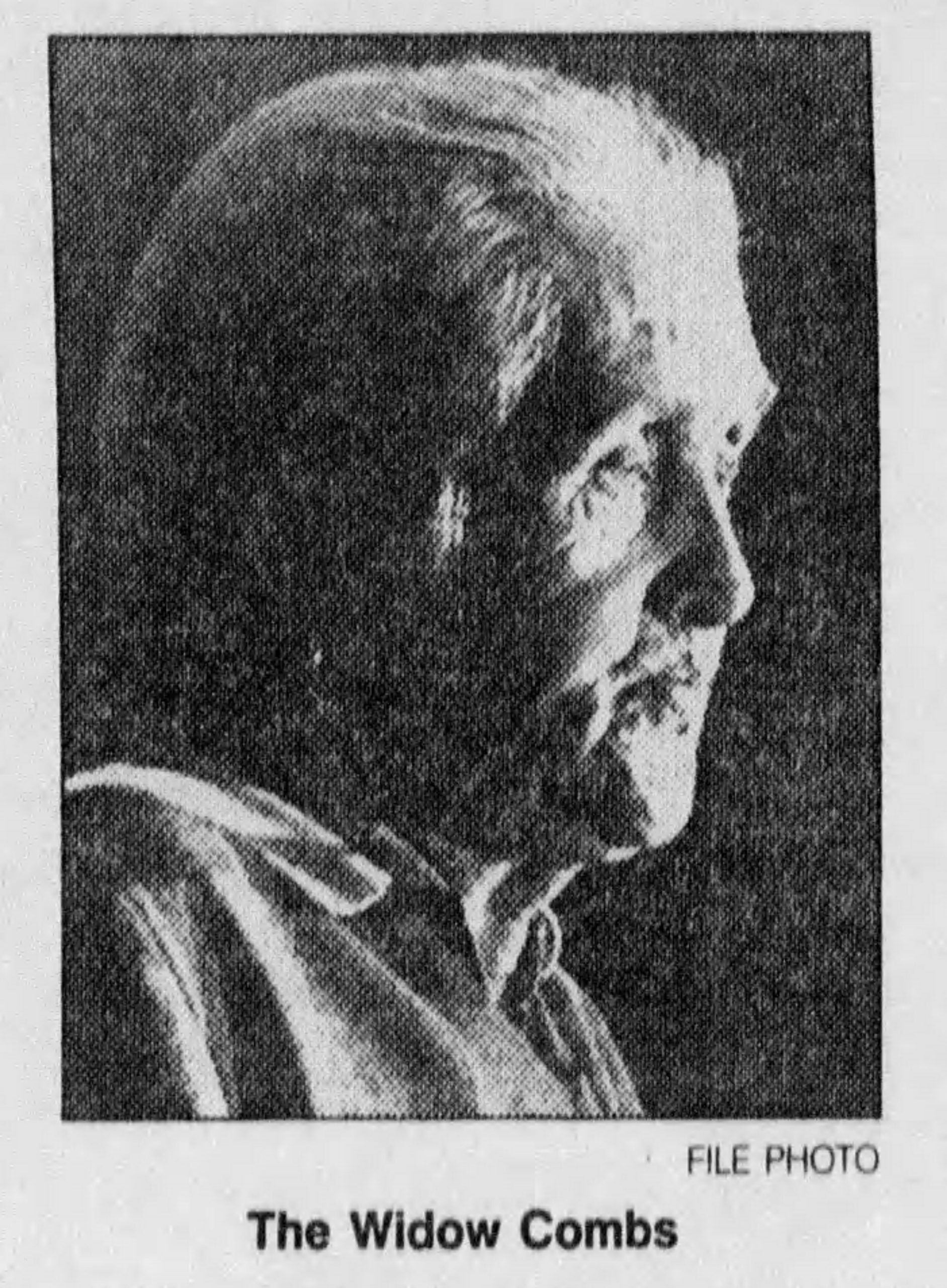

Ollie Combs was the sort of tough Appalachian woman that all of us who live here can recognize. She was born in 1904, in Knott County, deep in the Kentucky coalfields. We know little about her early life, but we can speculate. Like other women born in the Appalachian coalfields in that time, she witnessed her surroundings and her community change drastically. Until World War II, the people of Knott County were mostly farmers. They had coal, but no railroads or other roads to ship it out, so it was left beneath the mountains. Farming in Eastern Kentucky was never easy. It’s hard to plant crops, harvest, and raise livestock on steep hills and ridge tops. However, you could count on the labor of your hands to provide for your family. The men worked in the fields and the women tended to work around the homesteads. They raised children without the modern amenities parents today appreciate: clothes were washed by hand, food was cooked on coal or wood stoves and ovens. Babies were born at home, without the safety net of hospitals to protect the women and infants. It was tough, but it was often beautiful. The air was clean, the woods filled with life, and the stars shone beautifully at night. It’s the Appalachia most of us instinctively long for, the Appalachia Hazel Dickens sang about desperately missing.

After World War II, new roads opened up the farmland and the coal underneath it. Unfortunately for Knott County, this coincided with a major shift in the coal industry, from underground mining to strip mining. Instead of tunneling into the sides of hills, huge machines blasted and scraped away at the tops of them, removing debris and dumping it into creeks and ravines until the coal was exposed. Knott County also experienced the treachery of the broad-form deed. Knott County farmers were informed they only owned the surface of the land, not the minerals beneath it, and the coal companies had the right to take whatever means necessary to get to the coal. The cheapest, and easiest, way to get to the coal was to bulldoze through. Homes, barns, and graveyards were all leveled as the companies sought to get to the coal. The residents of Knott County watched as their family cemeteries, dating back generations, were ruined. One woman watched as the coffin of a child that died in infancy was ripped from the ground and sent tumbling over the hillside.

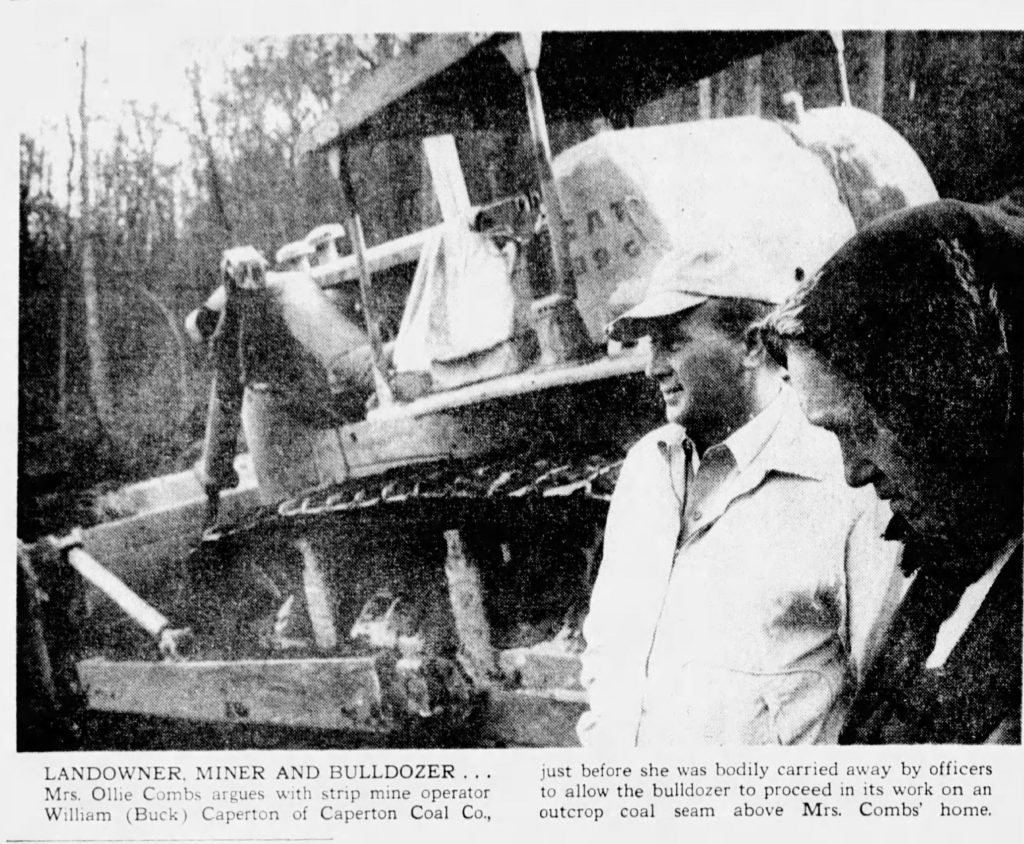

Ollie Combs watched all of this. Soon, the coal companies came for her farm. In March of 1965 she buried her husband. She had spent the past six years as a fulltime caregiver for her son Jimmy, after he was paralyzed in an automobile accident. In November of that year, bulldozers from the Caperton Coal Company arrived, ready to begin the work of tearing up her farm to access the coal beneath it. Earlier that year, a neighbor, Leroy Martin had unsuccessfully sued to keep the same from happening to his farm.

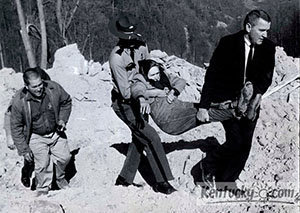

Ollie didn’t see the point in doing the same. Instead, on November 21, 1965, she sat down in front of the bulldozers and refused to move. Two of her sons were with her. The coal company obtained a restraining order from the local judge. The next day, they did the same. Despite the cajoling, arguing, and pleading of the dozer operators and coal company representatives, she stood her ground. That evening, she was arrested for trespassing on Caperton Coal Company property and violating the restraining order. At first, she cooperated with the police, but as they began the descent down the mountain she eventually became a deadweight. “I was just tryin’ to see how heavy I could be”, she later remembered. “I wanted to see what they would do. I didn’t think they would actually carry me off.”[1] Soon, the police were carrying her down the mountain and that image—of a frail elderly woman, bundled up in coat and headscarf, being forcibly removed from the home where she had known happiness and raised her children—was emblazoned across national newspapers. The photographer who took that famous picture, along with her sons, were also arrested.

At their hearing, Ollie and her sons freely admitted to forcibly blocking the coal company’s operations. Ollie told the judge that “I didn’t want to them to come through. I didn’t want to see my home ruined. It’s all I’ve got left.”[2] The trio were sentenced to 20 hours in jail, beginning on Wednesday, November 24th. To their credit, the Caperton lawyers objected, pointing out that the sentence would extend into the Thanksgiving holiday the next day. The judge remained firm, and another iconic image was captured: Ollie Combs, flanked by her sons, eating Thanksgiving dinner in a Knott County jail cell.

Combs became a figurehead for the fight against strip mining, not just in Knott County, but in Appalachia. Her method of resistance was repeated throughout the region as citizens continued to protest the destruction of their beloved homes. Ollie was interviewed and called as a witness in several hearings about strip mining, and many believe her experience to have been instrumental in the outlawing of the broad-form deed in Kentucky and, later, significant restrictions placed on strip mining.

Ollie, however, was still an older widow. She was strong of will and of body, but she was still 61 and raising a 13-year-old son and caring for another, permanently disabled, son. By 1975 she had “retired” from protesting, instead focusing on caring for her disabled son. Caperton Coal, inundated with terrible press following her arrest ten years earlier, had never bulldozed her property. In 1976, Ollie agreed to let the company (now Falcon Coal), to build a road through her property to mine on the hill above her home, provided they protect her house, appropriately compensate her, and get her a telephone line. They offered her sons jobs and agreed to plant an orchard for her on the mine above her home once it had undergone reclamation work. They offered to fly her disabled son to a specialty hospital for complete evaluation and treatment. After years of hard living, who could blame her for agreeing to these concessions? It was a very pragmatic decision, although not popular amongst many people who had continued to fight against strip mining.

Ollie died in 1993 at the age of 88 and was remembered in newspapers

around the country for her fight against strip mining. Instead of strip mining,

Falcon Coal company accessed the coal by her home the traditional way,

underground, and on the opposite sound of the mountain from her house. Ollie

Combs, like other strong Appalachian women, stood up for herself, her family,

and her community. Her protest and her fight was just as important, and just as

meaningful, as the fight of other Appalachian activists, although not taught as

broadly as the fight of other groups such as the coal miners. She’s an inspiration

to Appalachians everywhere, especially women. No matter your age, your

occupation, or your wealth, you can fight and make a difference in your

communities.

Sources

The Courier-Journal

The Messenger

“Chapter 7: Bullets and Bombs in Clear Creek”, by John Cheves and Bill Estep. Lexington Herald-Leader, https://www.kentucky.com/news/special-reports/fifty-years-of-night/article44430654.html.

[1] “Strip mining foe dead at 88″ The Messenger newspaper, Madisonville, Kentucky, February 26, 1993.

[2] “Thanksgiving in Knott Jail”, Bill Billiter. The Courier-Journal, Louisville, KY, November 25, 1965.