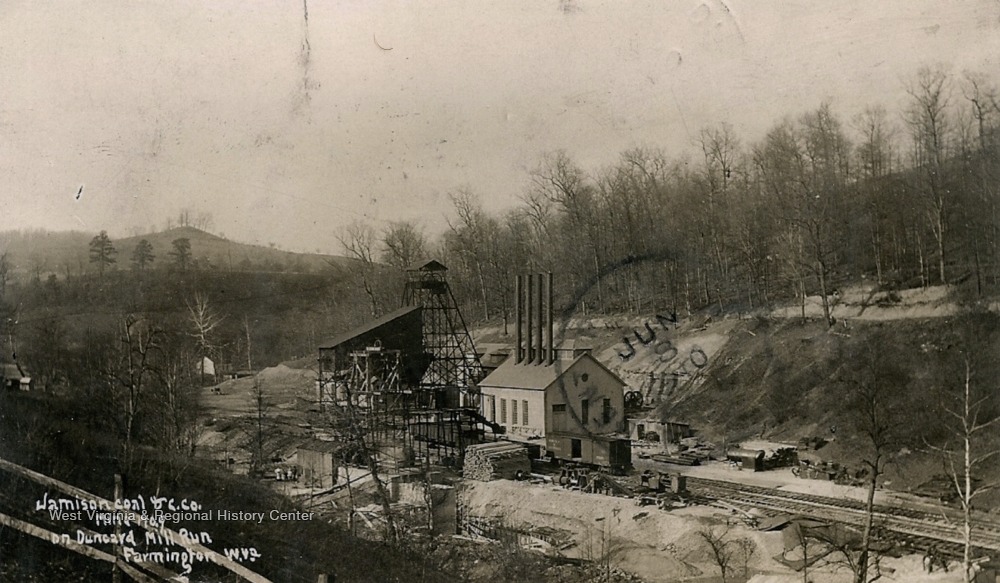

Sara Lee Kaznoski, Mary Kay Rogers, Mary Matish, and Norma Snyder all kissed their husbands goodbye on November 19th, 1968. It was not a particularly remarkable day for them. Their husbands had been miners for years. Sara’s husband, Pete, had first went into the mines at the age of 14. All three of the men worked in the No. 9 mine in Farmington, West Virginia. Despite the worsening conditions inside the mine, all three of them went to work that evening. They had to provide for their families. Pete had been voicing concerns about the heat inside the mine, the dust, the lack of ventilation, and the gas—all fuel for a massive explosion. However, the mine had been in this condition for months and they had been safe so far. The company, as has been documented many times over the years, was fully aware of the conditions of the mine and failed to act to make necessary safety improvements.

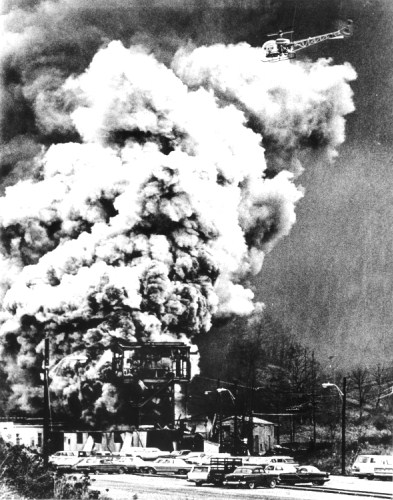

Sara set the table for Pete the next morning. He was always hungry when he came home from work, and she had made him a big breakfast. She turned on the TV to the news, and her stomach dropped. All local and national news stations were reporting an explosion at a mine in Farmington, West Virginia. The No. 9 mine. She never saw Pete again. He was among 78 miners killed when the dangerous conditions finally ignited a massive explosion that tore through the miner. Pete’s body was never recovered.

For days, Mary was hopeful that her husband would somehow be found, miraculously alive. She just couldn’t shake the notion that he had just went off to work and would just be home late. She couldn’t accept that he was entombed in the mine with so many other men. But at least Mary, and Norma, were able to bury their husbands, small consolation that it was.

When tragedy strikes, people have a variety of responses. Some people are overwhelmed by grief and settle into it. There’s nothing wrong with that. Some people suppress it and just try to go on with their lives, taking care of who’s left behind and throwing themselves into the realities of everyday life. And some people get angry, very angry, and use that anger to force the powers that be to act to prevent such a tragedy never happens again. The widows of Farmington, led by Sara Kaznoski, did just that.

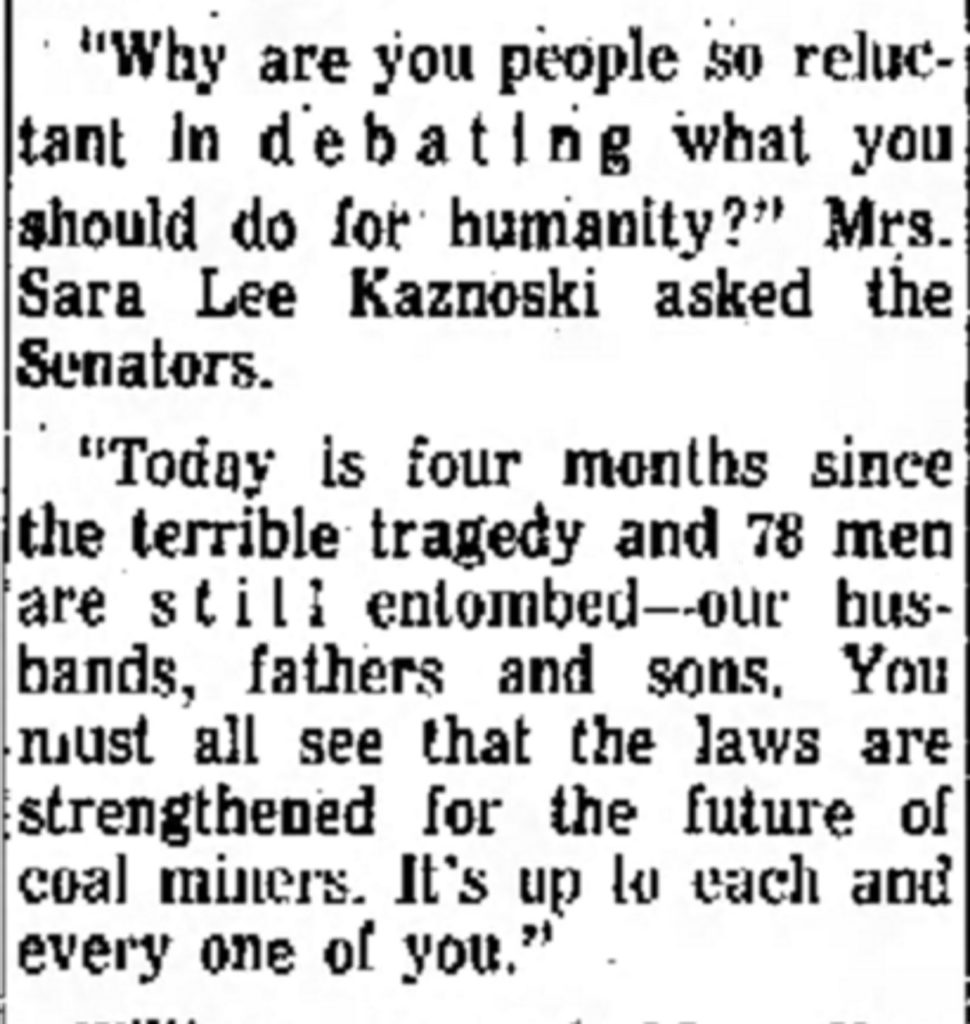

In January 1969, Kaznoski and the other widows formed the Widows Mine Disaster Committee to force the government to hold Consol Coal Company responsible for the disaster, recover the bodies of the miners, and pass legislation to prevent future such tragedies. They were inspired by the actions of Miners for Democracy, the Black Lung Association, and the actions of Representative Ken Hechler (representative from West Virginia) to improve the lives of miners in the state. Rep. Hechler invited them to testify in Congress, sharing their grief and anger over the preventable explosion. For the women, widows and housewives who had lived their lives in rural West Virginia, it was an overwhelming experience. However, they steeled their resolve and traveled to Washington to make sure that the world knew what they had lost and who was responsible.

The widows didn’t just want to prevent accidents. They wanted all miners to work in conditions that were as safe as possible, conditions their husbands had never experienced. They wanted roofs to be shored up, lung disease to be diagnosed and treated early, dust and gas levels to be minimized. Congress listened and passed the Mine Health and Safety Act in December of 1969, which set out explicit safety regulations in mines nationwide. President Nixon announced his intentions to veto it, citing concerns over the cost of black lung compensation. The Farmington Widows Mine Disaster Committee, by now a respected activist group throughout the United States coalfields, urged miners to protest, and this time for the protest to extend throughout the country and not just in Central Appalachia. It seemed that the year was going to end the way that it began, with mass wildcat strikes that would hit the nation’s heating fuels in the midst of winter. Nixon relented and signed the Act on December 31, 1969.

Kaznoski’s activism didn’t stop at the fight for health and safety legislation. She became involved in the internal struggle of the UMWA to cleanse its top leadership of corruption, rallying in support of Jock Yablonski, who was looking to unseat Tony Boyle as the head of the UMWA. Boyle had made no friends in Farmington and had even praised Consol Coal company immediately after the explosion. She received death threats for these efforts, although it was Yablonski who was ultimately assassinated at the hands of Tony Boyle and his supporters.

There is no correct way to grieve. It is as personal and variable as any of aspect of someone’s personality. Tragedies such as that that rocked Farmington in November of 1968 often seem pointless and senseless. However, after spending their lives watching these tragedies unfold in mine after mine, in West Virginia and around the country, the widows of Farmington were galvanized. They refused to let the death of their loved ones be another senseless sacrifice to the greed of the coal companies. Their fight would forever change the mining industry and has spared thousands of men and women from violent deaths and permanent disability.

The people of Appalachia are often written off as fatalistic, passive participants in their lives. We just let things happen to us, accept the disparities, and never act to make things better. This is simply not true, and even in the midst of crushing grief we find the strength to fight back. This was true in 1969 and it’s true today. We don’t have to accept anything, and our true legacy is that of the striking miner or the adventurous mountaineer—not the broken-down, impoverished, intolerant, poorly-educated caricature the rest of the country wants us to be.

References:

Bonnie Stewart. No. 9: The 1968 Farmington Mine Disaster. West Virginia University Press, 2011.

We all knew that mine was terribly unsafe but little did we know at that time that a boss at number 9 would actually order two electricians to sever the warning wire to the fan , that would have alerted the miners to get out the fan was down. By the time we found this out and who those two men were the courts told us the statute of limitations had ran out. But in the end we finally knew what caused this explosion and who was guilty. It still never made life any easier for 19 of us whose husband is still entombed there. Just imagine the torment those two men lived with the rest of their lives. A few of we widows had been at a rally just a short time before Jablonski was murdered by Tony Boyles henchmen. Such a terrible tragedy.

This article is so awesome!!!