It was early in the morning on November 20, 1968 when an explosion rocked the small town of Farmington, West Virginia. It was powerful enough to be felt miles away, in the larger city of Fairmont. Miners and their families lived in fear of the sound of an explosion and the blaring of the alarm at the mines. It meant a terrible accident. In 1969, it meant there would be fatalities.

The region was no stranger to mining disasters. In 1907, only six miles away, the Monongah mine disaster claimed the lives of over 300 men. Until then, the coal industry was essentially unregulated and companies had no legal obligation to ensure safe working conditions for miners. The horrific scenes from Monongah spurred the region’s leaders into actions. It was from Monongah that the United States Bureau of Mines was born.

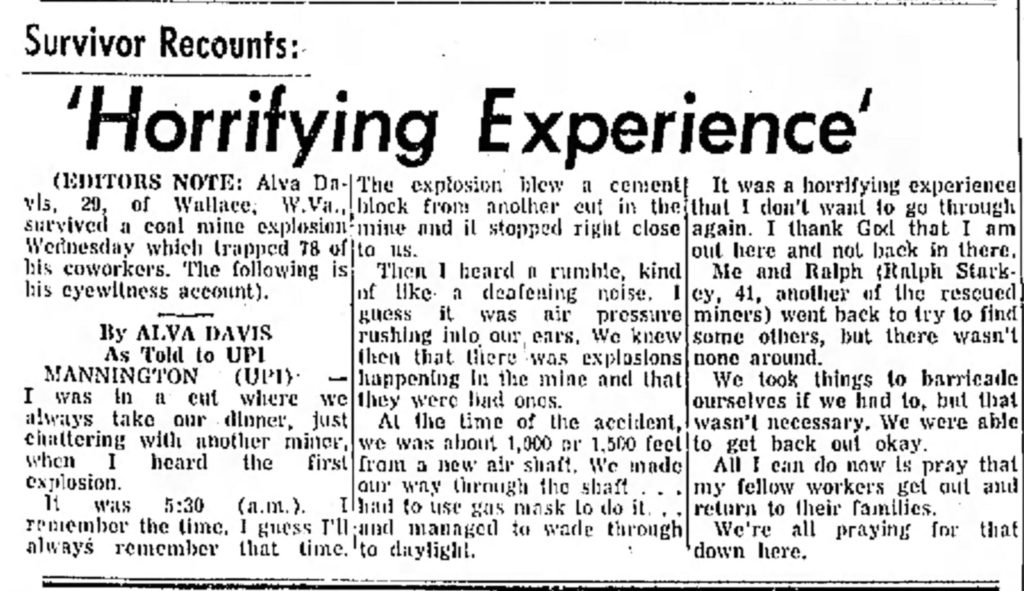

By 1968, things had improved. Accidents were down and it was rare to have mass-casualty disasters. These had been commonplace at the beginning of the century. However, there were still significant loopholes and gaps in labor law. This allowed the unsafe working conditions that directly contributed to the explosion that rocked the Consol No. 9 mine in Farmington, killing 78 miners.

In the months and years after the disaster, the community of Farmington came together. The widows leveraged their grief into activism and Congress into action, just as it had in 1907. This time, it culminated in the 1969 Coal Mine Health and Safety Act which drastically improved mine safety while also providing protection for miners suffering from black lung.

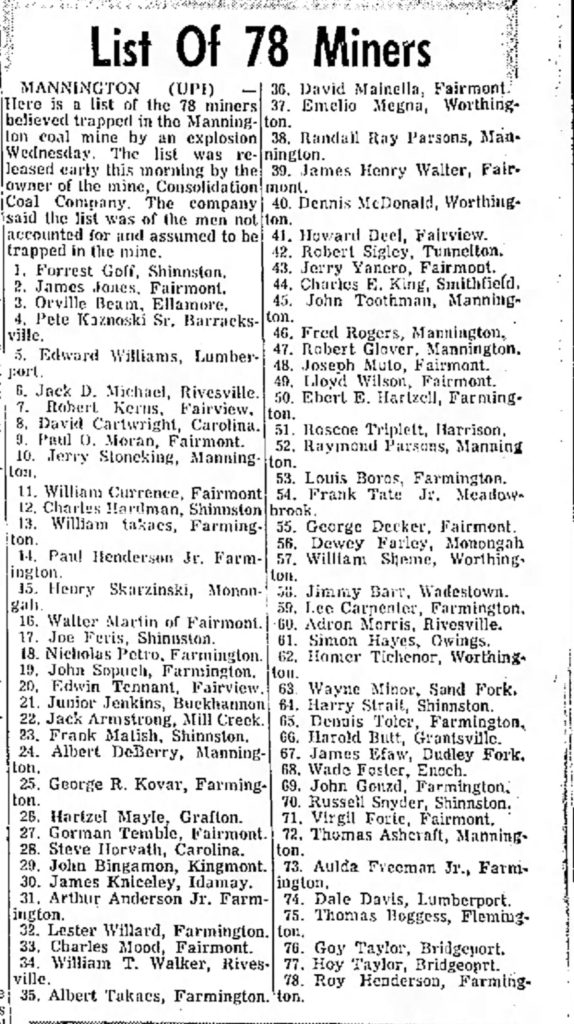

78 men went to work on the evening of November 19, 1968. They never came home. They left behind families, friends, and coworkers. Their deaths were unnecessary and preventable. The only small consolation in their deaths is that, ultimately, they were not in vain. They did not choose to become martyrs in the cause of miners’ safety, but the shock of their demises directly improved the safety of the miners left behind.

So, on November 20th, take time to think about Farmington No. 9. Remember the 78 men who lost their lives underground, and appreciate the work of their surviving family members in making sure it would never happen again.

Rember it well…sad day!