Why Epidemics?

I’ve been mulling over what I would write next for a couple months now. When COVID19 hit, I was in the middle of a series on Appalachian women. However, COVID has made me think about other diseases our society has faced. Diseases strike Appalachia hard. We tend to start out already being pummeled by a mountain of socioeconomic hits. When a disease hits us, we’re already weakened by poverty, a small healthcare infrastructure, and other chronic conditions. If COVID gets into Appalachia like it has in New York or other hot spots we will suffer disproportionately. Appalachia has faced other epidemics in the past. We have beaten other epidemics in the past. Some epidemics we are still fighting. My aim with this series is to explore how Appalachian communities have risen to the challenge of fighting back against disease and inspire us to fight back against this latest one.

As a physician, COVID has been particularly worrisome. I understand all too well how deadly it can be. I’m in several physician social media groups. They are filled with other physicians describing their patients, the colleagues that have come down with it, their own experiences with the disease. My extensive infection control education helps me understand and appreciate how this invisible virus can cause so much damage. As I have watched this new disease unfold, it has reminded me of many other diseases. Measles, Polio, HIV: all diseases that have swept our populations and that required intense efforts by the medical community and our leaders to bring under control.

Why tuberculosis?

For decades, the deadliest respiratory disease in Appalachia was tuberculosis. This bacterium wiped out entire families. Today, we scarcely think of it. Most of us have had the experience of having a PPD screening test. Because it is such a contagious disease, individuals who work with the public in certain roles are required to have these tests done. Healthcare workers get them regularly, food service workers must get them as part of obtaining their food handlers certification. However, few of us, especially those of us born in the 1970s or later, have ever actually known someone with tuberculosis. It’s become a disease we simply don’t worry about, when once it was a feared and deadly disease. For all of these reasons, tuberculosis seems like the best place to start with this new series.

The pathology and history of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is a disease caused by a bacteria called Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It spreads by infected respiratory droplets, much like COVID. When people cough, sneeze, sing, spit or talk, they release the bacteria into the air. The bacteria are then inhaled into the lungs, where they settle into the small airways. The lung’s immune responses cannot destroy it, and this causes scarring and destruction of lung tissue, creating holes in the lungs. The bacteria can also enter into the blood stream through the lungs, and infect other parts of the body. Some people live many years, even their entire lives, with an inactive tuberculosis infection. They have the bacteria but it never causes widespread lung damage or damage to other body parts. Their immune system can contain it. However, other people have worsening lung damage. Eventually they get to the point where they develop what used to be known as consumption: terrible coughing in which they cough up blood. Without treatment, these people will die.

Tuberculosis is not a new disease. Evidence of it has been found in Ancient Egyptian mummies. However, the disease took off during and after the Industrial Revolution. Poor people moved away from farms with low population density into cramped urban areas. Already weakened by malnutrition and long hours at work, they became very susceptible to the disease. This was also true in Appalachia. By 1900, many Appalachians were living in crowded coal camps or factory towns, experiencing the same kind of poor living conditions that workers experienced in urban areas. Additionally, they were often exposed to fumes at work that weakened their lungs.

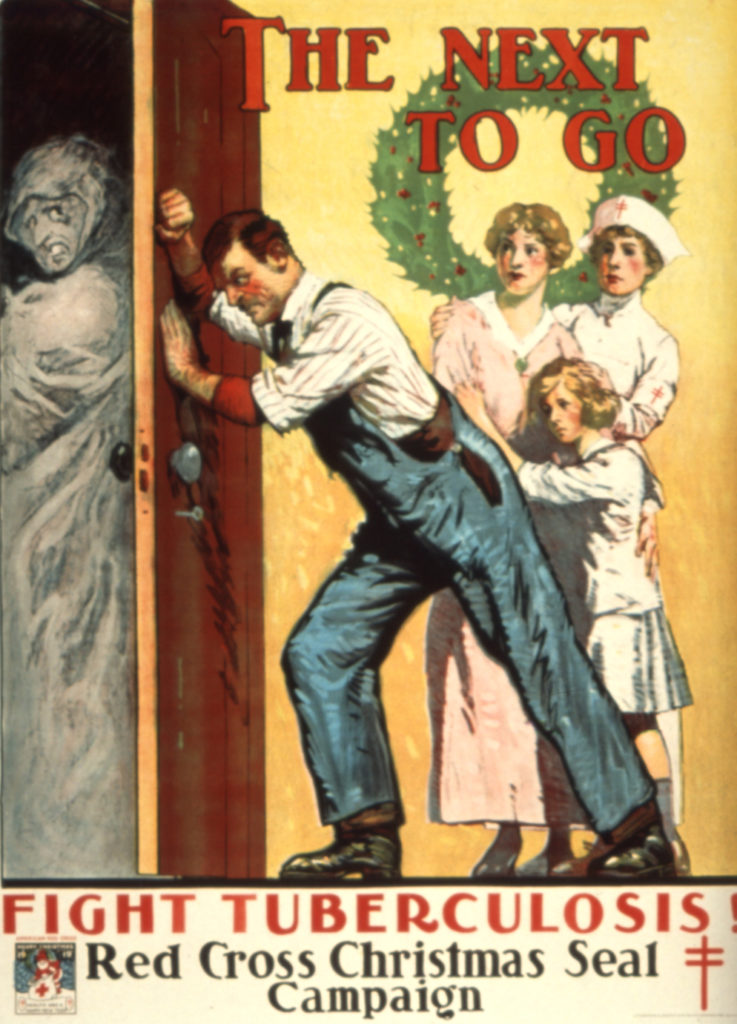

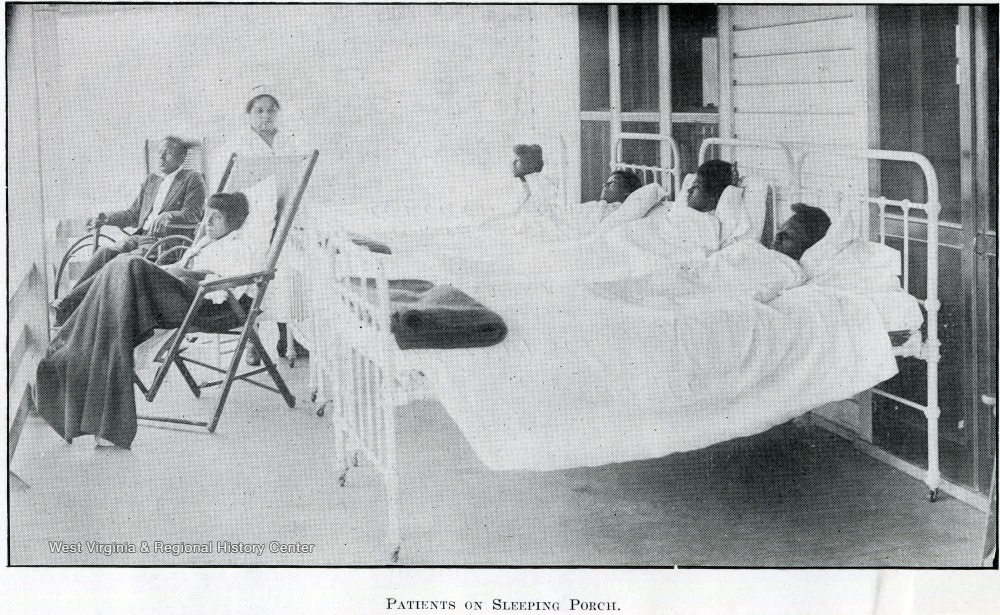

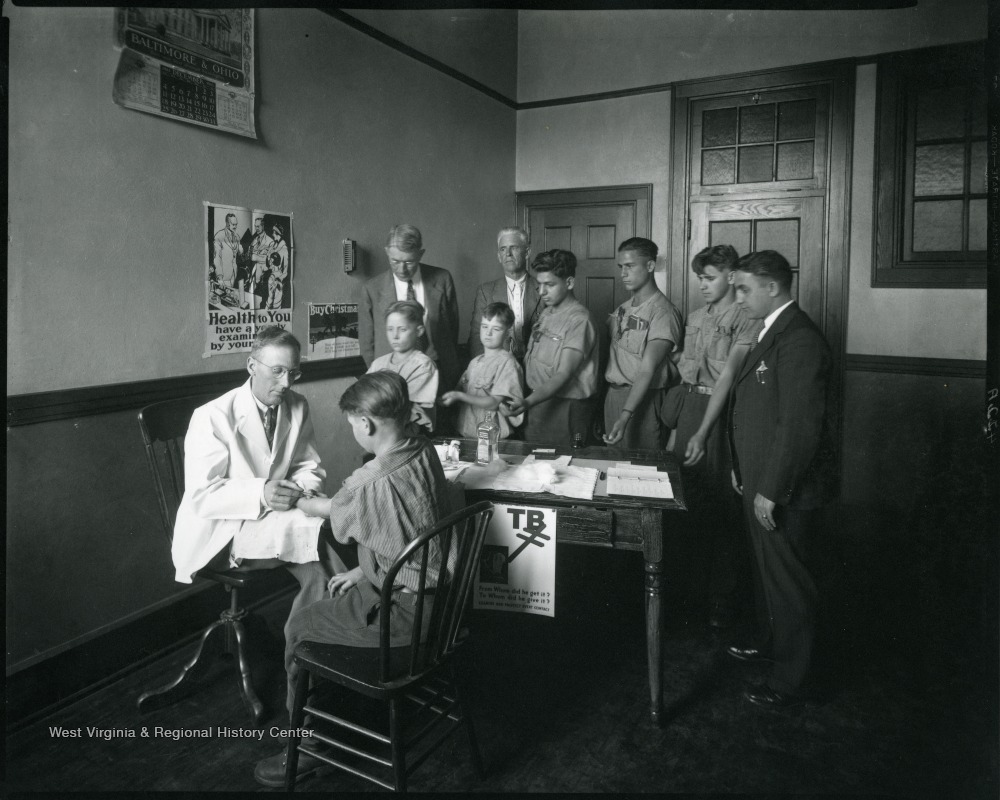

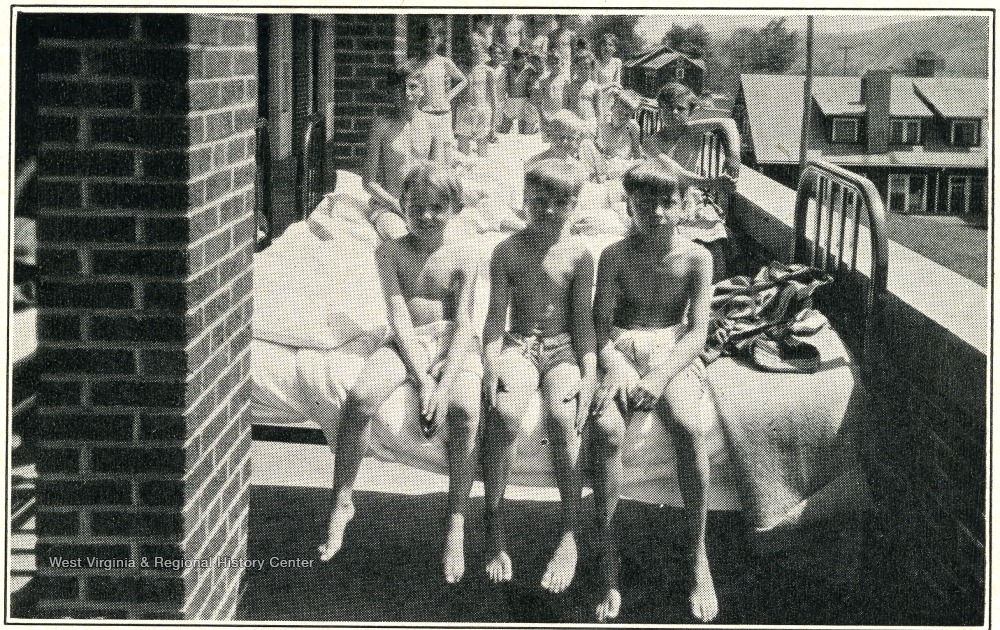

Early treatment efforts

Initially, the approach to tuberculosis was containment. Once an infected individual was identified, it was recommended that he or she enter into a specialized facility or sanitarium. This would serve to isolate them from healthy and non-infected individuals stopping the disease transmission. This would also ensure that the patient received good nutrition and medical care and could potentially recover from the disease. Sanitariums were established throughout Appalachia, segregated by race. In West Virginia, the most prominent were the Hopemont Sanitarium in Terra Alta (established by West Virginia’s first female physician, Harriet Jones) and the Denmar Sanitarium which was for African-American patients only. Despite these measures it was still widespread in Appalachia and thousands of people died yearly from it. It was a greatly feared diagnosis because it was so often fatal.

Post-war improvements

In the late 1940s, it began to change. In 1947, the United States Coal Mines Administration released a report on the health conditions of the soft-coal mining areas in the country; this followed an extensive health survey. This report, now known as the Boone Report (after the Rear Admiral who directed the survey team) was a shocking publication. It detailed, in depth, the numerous healthcare deficiencies experienced by those living in the coalfields. It especially focused on the lack of good public health education and infrastructure. It was common to drink raw, unpasteurized milk known to spread disease such as tuberculosis. Restaurant workers were not tested for diseases. Additionally, the report survey team discovered that most places lacked widespread tuberculosis surveillance programs which allowed the disease to spread unchecked throughout the communities. The mortality rates for tuberculosis were higher in the coalfields than elsewhere in the country.

The report also blamed coalfield doctors, especially those employed by coal companies, for failing to adequately promote public health in their communities. It also blamed the UMWA for not advocating for better public health. The UMWA took the findings of the report very seriously. At this time, they were working on the establishment of a coalfield medical program to deliver free healthcare to miners and their dependents. A driving motivation behind their efforts were to improve the health conditions of the miners, including treatment of tuberculosis. This program, the UMWA Welfare and Retirement Fund, greatly expanded access to medical care in the coalfield communities. It actively monitored the quality of healthcare delivery and reported physicians who were practicing substandard medicine. As a result, the health of the coalfield citizens improved, including a decrease in tuberculosis

The Appalachian Regional Commission

The biggest improvements in tuberculosis management in Appalachia happened as a result of the Appalachian Regional Development Act (ARDA) of 1965. In 1960, the Presidential campaign had shone a bright spotlight on Appalachia. For the first time, national news broadcast images of Appalachian poverty into homes nationwide. For better or for worse, the issues of Appalachia became a national project. In 1965, as part of his War on Poverty initiatives, President Johnson pushed for the passage of the ARDA, which in turn created the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). The ARC, which still exists today, was directed to perform a comprehensive evaluation and improvement campaign of Appalachia and work to erase the numerous disparities faced by Appalachian citizens.

One of the ARC’s top priorities was an improvement in public health. It launched numerous public health programs, including a large tuberculosis program. Public health services were greatly expanded. Health departments finally had the resources to identify and contain tuberculosis. They followed the principles of “contact tracing” to identify positive cases and those who had been in contact with the cases. Medical science had also progressed to the point that there were now effective treatments for tuberculosis. While not the most pleasant of medications to take, with numerous side effects, they are successful at curing people of tuberculosis. The ARC health programs expanded access to testing, contact tracing of known and suspected cases, and treatment for the disease: all key portions of controlling an epidemic. Another very important component of this was that the citizens of Appalachia cooperated. They understood how serious this disease was and how it had affected their communities. They worked with the health authorities even when it meant they faced long-term hospitalizations. They did this to protect themselves and their communities.

Tuberculosis today

Today, the tuberculosis rate is extremely low in Appalachia. Our public health infrastructure now has decades of experience with screening, tracing, and treatment of the disease. No widespread outbreaks have happened in decades. The lessons of tuberculosis should be applied to the fight against COVID. We should fight to make sure that our public health infrastructure is expanded to have the same response that it has had to tuberculosis. We should fight to make sure we have a good treatment and vaccine that will save lives. We should expect ourselves to rise to the occasion like we did with tuberculosis. Masks aren’t comfortable, staying home can be boring, and public health authorities questioning you can feel like a police interrogation. Appalachians are tough, though, and we care about our communities. We care about our aunts with diabetes and our mawmaws with COPD and our brothers with high blood pressure. We need to reach into the same place in our culture that allowed us to fight the tuberculosis epidemic and apply it to COVID. There is no reason why this disease should attack us the way tuberculosis did. If we act now we can make sure that it doesn’t.

My mother was one of those people who contracted tb. She passed away at the age of 23. My grandmother‘s family lived in Genoa, West Virginia. It wasn’t a coal field. Rather, they had a very nice home very clean so for whatever reason she did get it and it took her life.

I am so sorry to hear that you lose your mother so early. A common source of tuberculosis has been raw milk–that could very well have been where she got it. Pasteurization of milk was not universal in West Virginia until well into the 20th century.