Stereotypes and Reality

I’ve debated covering this topic for some time now. I know that this is an important piece of our region’s history. It’s an important driving force behind so many of our epidemics, but I didn’t even know how to begin to attack it. I also wasn’t sure that I wanted to address it. Many of the negative stereotypes of Appalachia center around the image of an uneducated, impoverished, barefoot person who is clearly an “other” in American society. This notion of Appalachia, Appalachian poverty, goes back at least to the last half of the nineteenth century. It allowed well-intentioned reformers justification for their projects in the region. It also gave the timber and coal barons a justification for their takeover: Appalachia, like other colonies in history, needed the guiding influence of their superiors to fully attain the urban, western ideal of civilization.

My challenge, then, has been how to address this entrenched epidemic without bolstering this classist, paternalistic stereotype of my beloved Appalachia. I’m certainly not going to be able to tell a comprehensive history of poverty in Appalachia in a single blog post. However, I think it’s important for Appalachians–especially those of us who have personally known poverty–to contribute to this narrative. It’s important for us to have a hand in shaping how our story is told. It’s important not just for the sake of fairness but also for the sake of truth. A history that leaves out the perspective of its subjects themselves is not a full history.

Poverty Before 1900

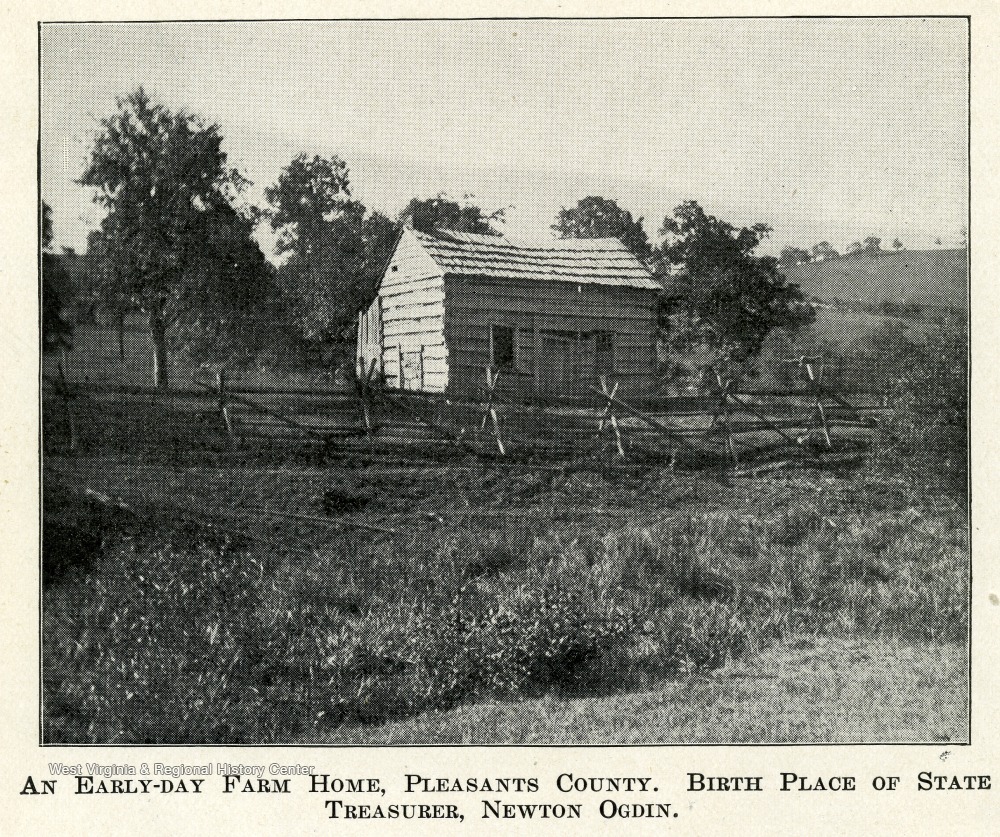

It’s difficult to say when Appalachian poverty became so ingrained in our region. We know that the frontier settlers of the late 1700s and first decades of the 1800s lived a difficult life. They came into Appalachia, crossing the ridges and toiling through the valleys, hacking their way through an enormous virgin forest. They depended overwhelmingly on their own labor to meet all of their needs. Does this make them impoverished, however? Would they have considered themselves to be mired in poverty, to be of low socioeconomic status? Were they that different from other families in America? Would we only consider them impoverished using a Western, post-industrial definition of poverty?

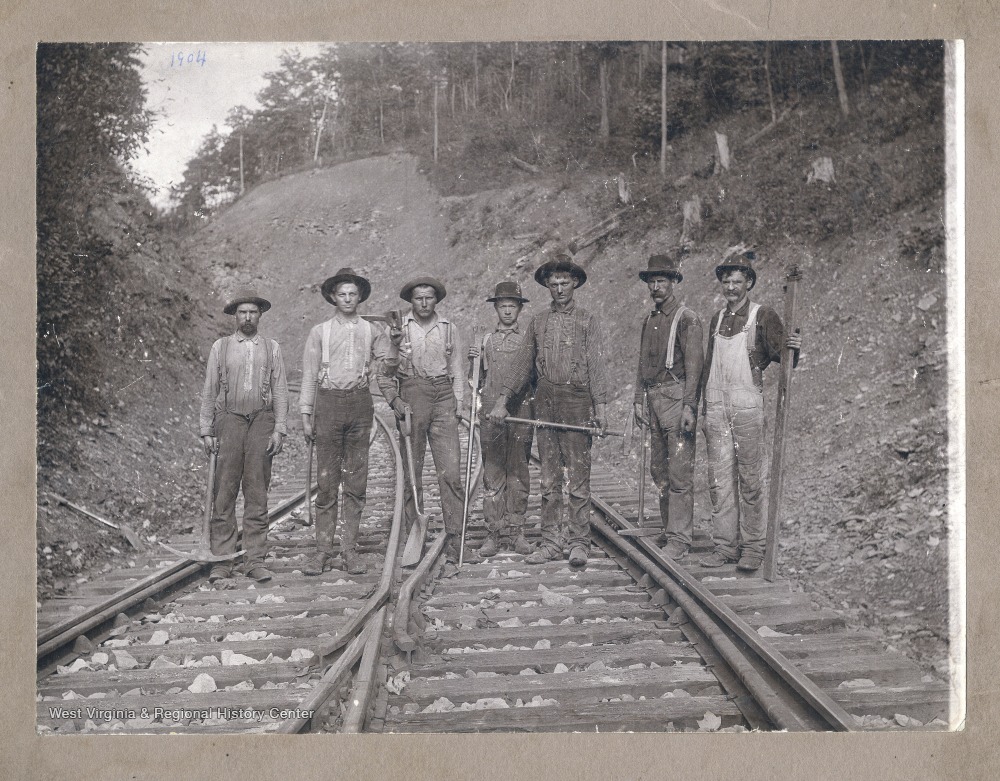

We also know some things about the time period during which the railroads arrive in the Appalachian interior. We know that there was a perceived disconnect between industrial American consumer culture. Urban America by this point had many of the features we would recognize today: mass production of consumer goods, catalogs, theaters, sports, public transport, etc. Appalachia did not have this. As mentioned in a previous post, the railroads opened up an entirely new market for entrepreneurs. They found communities for which this new consumer culture was new. Even in this time period, ideas of civilization and progress were tied to consumption. They focused on buying the ideas, goods, and services manufactured in the industrial centers of the country. Appalachians mostly did not take part in this. The rest of the country thus place them in a different, “backwards” category.

It wasn’t just the consumerism that created this idea of Appalachia as a poverty-stricken region. It genuinely did lag behind the country in things such as infrastructure and medicine. So, when the railroads opened up the region for the timber and coal industries, they created a new narrative. Appalachia was lagging behind in goods and services, lacking modern civil infrastructure, education, and medicine. The timber and coal industries, and the outside teachers, doctors, and missionaries they would bring in, were necessary to help bring Appalachian towns in line with the rest of the country.

The 20th Century

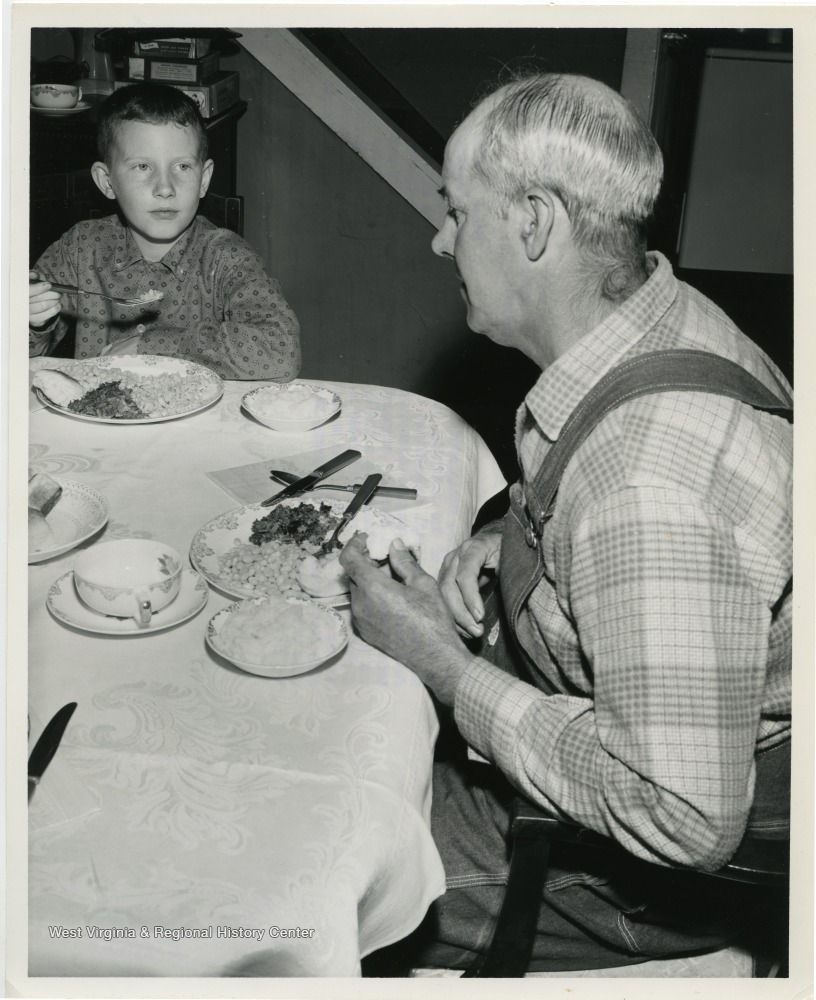

Most of us know how this turned out. The industries, through the use of the broad-form deed, were able to take huge tracts of land away from the people that had lived there for generations. Deprived of their traditional livelihoods, they relied on the timber and coal companies to provide them with food, living wages, and shelter. Because extractive industries such as coal are boom-and-bust industries subject to international forces, times of want followed prosperty. Because these industries were able to control the state governments, the governments didn’t tax them. Appalachian communities became colonies of the rest of the country: exploited for natural resources with the native inhabitants seeing little of this wealth in return.

The coal industry hit its slow, persistent decline in the Depression. There were brief upticks during World War II, but the postwar period and beyond saw the emergence of natural gas and other forms of energy production. These new industries pulled out the rug from under Appalachian towns and governments. They never fully recovered.

By the 1960s, Appalachian poverty was undeniable and became the symbol of progressive social welfare programs such as The War on Poverty. This spurred the creation of programs such as the Appalachian Regional Commission, which we have discussed a great deal in this series. However, despite its efforts to improve education, health, and infrastructure the goal of eradicating Appalachian poverty remains elusive. Poverty still plagues the region, and this social determinant of health directly contributes to all of our new Appalachian epidemics: Diabetes, Heart Disease, Cancer, Opioid Addiction, Lung Disease.

Finding a Cure

A lot of people have a lot of different opinions on how to fix Appalachian poverty. It’s a major platform feature of any politician who wants to be successful here. Some politicians favor cutting natural gas and coal taxes with the hope that the increased profits will find its way into the pockets of their constituents. Others promote retraining programs or enhanced educational opportunities. I think the best way to finally beat this epidemic will require a multifactorial approach. We need broadband, good roads, childcare for working families, educational subsidies, major investments in our public schools, and continued improvement in our health access. A minimum income program would also make an enormous difference.

Poverty is our biggest modern epidemic in Appalachia. Unfortunately, it is going to be an epidemic that affects more and more communities around the country as the longterm fallout of COVID-19 continues. If we don’t defeat poverty, we’ll likely never the other modern health crises facing us. We need to prioritize the eradication of poverty as a major goal in our country and in our region. It’s how we’ll finally reverse the damage caused by the unfettered capitalism of the last 150 years.

This is so true being a WV hilly was a bad thing in the50s it took me until the 80s and a lot of study to be able to say My father was an uneducated not ignorant coal miner and I am proud of the heritage he left me. Well put Mollie

Some of the most brilliant people to ever live are from WV. We always got a bad rap. LOL

In the 60’s I was in the US Navy and listening to Mozart on the radio aboard my ship and

my friend from NJ was shocked that people from WV had ever heard of Mozart…LOL

I used to tell them we received the same radio waves they did, but it just took a day longer

for them to get back in the “hollers” where we lived…

AS usual, excellent article Mollie!