Six-Dollar Grapes

In Morgantown there is a very large Kroger which the locals jokingly refer to as “Gucci Kroger”. It has a Starbucks, a huge international food section, aisles of vegan/vegetarian food, healthy meal-prep sections, a large meat and seafood counter, and a variety of organic and locally-sourced dairy and egg products. The produce section is correspondingly impressive and you can buy fruits and vegetables there you can’t get anywhere else in town. On Saturday mornings, there is also a farmer’s market in downtown Morgantown. You can buy pasture-raised beef and pork, locally-grown vegetables, and farm-fresh eggs.

I have a friend that is a coalfield physician in southern West Virginia. She had to stop buying grapes at her local grocery store for some time because they topping out at $6 a bag for regular seedless red grapes. Currently, the Kroger mentioned above has them for $1.99 a pound. There are also no farmer’s markets in her community.

Any primary care physician in Appalachia can speak to the great cost of obtaining and consuming healthy foods. In a community where a frozen pizza costs $1 but a head of broccoli costs $5, it’s not difficult to see where people will be forced to spend their limited food budgets. Food pantries exist and are sadly becoming more vital due to the current economic recession, but they are also limited. They must use non-perishable, pre-packaged foods to ensure maximum shelf life. These are often high in fat and salt.

Summer gardens are a common sight in Appalachia, but also require financial investment. It takes money to deer-proof the garden, buy the plants and seeds, buy the stakes for the beans and tomato plants. It takes money to purchase jars and lids to preserve the produce. It takes more money to buy the canning equipment required to process it safely. Plus, you have to own your own plot of land. These may not seem like big barriers, but for many low-income and rural Appalachians they are enormous hurdles to overcome.

Malnutrition in the Industrialized World

Food insecurity and malnutrition is not something we often think of with respect to today’s Appalachia. For one, the popular perception in America is that malnutrition is not something that happens in our country. Our perceptions of malnutrition tend to skew heavily towards the developing world. These perceptions are often helped along by commercials for missions and charitable organizations seeking to fund childhood nutrition programs overseas. In America, we also tend to visualize malnourished people as very thin and emaciated. Appalachia, with its high prevalence of obesity, does not fit into that picture. However, nutritional status does not equate with weight, and an obese person can suffer malnutrition in the same way that an underweight person can. The obese Appalachian, however, is blamed for this health status. Obesity is thought of as a personal failing and not a complex physiological disease process.

So, for this post, I’m going to focus on the Appalachian epidemic of malnutrition. It’s one of the few epidemics that has not seen a significant improvement over the past century. It has simply changed its presentation. In fact, some studies indicate that more rural Americans—including Appalachian—deal with food insecurity and malnutrition than either their suburban or their urban counterparts. Also, a side note: while malnutrition has distinct clinical criteria, for simplicity I am going to use the term “malnutrition” to refer to the general deficit of healthy food options in Appalachia. This could mean food insecurity, meaning not enough food, or issues accessing healthy foods like fruits and vegetables.

Historic Food Patterns

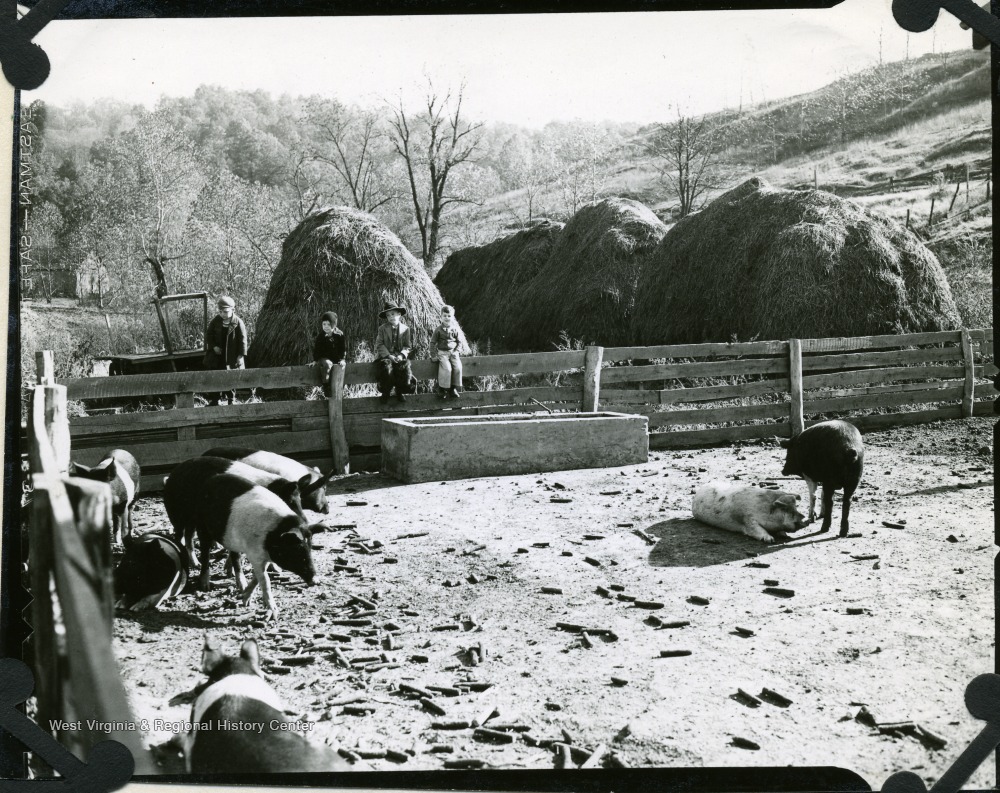

Appalachia was very much the frontier until the closing decades of the 19th Century. Even as the West fell victim to American colonialization, the terrain of Appalachia kept its communities isolated. Most families relied on subsistence farming, which was very difficult. It is difficult to grow crops on the sides of steep hills, but they managed. They raised cattle, poultry, pigs, and other animals. They hunted for deer and turkey and fished in the pristine streams. In many places in Appalachia, pockets of this way of life persisted well into the 20th century. My father, born in 1944, has vivid memories of his early childhood on an isolated farm in Braxton County, West Virginia. He remembers helping his grandfather in the fields and also remembers his grandfather carefully packing eggs in his saddlebags before leaving for town to sell them.

Industrialization changed all of this. In the coalfields, the family farms simply ceased to exist overnight as the coal and timber companies took them. In other parts of the state, manufacturing such as the glass factories of central West Virginia pulled people away from the land. They lost that critical link to farming and agriculture and began to depend more heavily on store-bought foods. This, by itself, is not necessarily a problem. However, it is a significant problem if the local stores do not carry nutritionally-sound food and if you can’t afford those foods.

In the coal camps, this was an especially large problem. All of the surrounding countryside was owned by the companies, and you could not legally hunt for lean game to supplement your diet. The Boone Report summarized the food situation in Appalachia well. While some statements are specific to the coalfields, the overall scene is applicable to all of Appalachia:

“[The miner’s wife] buys what is most readily available in the company store, or the small, competitive, independent grocery, where she does the major share of her shopping. Canned goods and dried foods comprise a substantial part of nearly every home meal. Sausage meats beef and pork cuts, especially chops and fat back, are frequently found on her table, but lamb and mutton are seen less often. Potatoes, if they are cheap enough, and some fresh vegetables when in season supplement the menu.”

Appalachian Food Today

This traditional Appalachian diet is delicious, but not always healthy. As a lifelong Appalachian, few foods make me happier than biscuits and gravy with eggs fried in bacon grease. Memories of my childhood and of my grandparents are strongly tied to memories of mealtimes with chicken and dumplins, or blackberry cobbler made with blackberries my grandma picked along our driveway, and big breakfasts of pancakes. However, the picture painted above by the Boone Report in the 1940s persists to this day. It has worsened in many (perhaps even most) communities throughout Appalachia. As rural communities lost population, they also lost large and varied grocery stores and markets.

Now, Appalachian communities face the paradox of having more grocery stores than average, but the stores are small without variety in their food offering. Growing up, my family faced a minimum drive of 30 minutes to get to the nearest grocery store. Many of my classmates in elementary schools had 45-60 minute drives one way. Longer distances to the store means the price is higher from the outset. You use more fuel just to get to the store. Food companies charge higher prices to get food into more isolated communities, so even when you get to the store everything is more expensive than it used to be. You have to stretch your food budget and buy foods that will last the 2-3 weeks between trips to the store. This means that lean meats and fresh produce are not going to make it into the cart a lot of the time.

We understand more and more that many foods in America promote obesity. Unfortunately, a lot of those are the same foods that are the cheapest and most available in Appalachian grocery stores. It is a key driving force behind the high rates of obesity in Appalachia, especially among low-income individuals. It’s simply too expensive and difficult to eat otherwise. This means that, as Appalachians, we develop insulin resistance and increased fat tissue that makes it very difficult to lose the weight when we try. We develop cholesterol issues. We are then at increased risk of diabetes, heart disease, fatty liver disease, and cancer. We lose more time to disability and illness, which further worsens our economic situation. It’s all linked and this very important issue of food impacts our region in enormous ways.

Unfortunately, it does not appear that easy solutions to this are forthcoming. The general lack of a social safety net in our country means that Appalachian citizens don’t have the resources and support to easily obtain healthy foods. It contributes to our persistent socioeconomic and health disparities and prevents us from reaching our full potential as a region. There are ways to fix this. Improving access to fresh produce and developing culturally-sensitive nutritional plans (that don’t completely outlaw traditional foods) are just two ways we can remediate the issue. Like many other issues facing Appalachia, we need to decide that our food status matters and demand our elected officials prioritize it. If we can force the coal companies to allow unions, we can certainly handle this.