- Harrison County Mayors Discuss Fixing West Virginia Roads[1]

- West Virginia Officials: Staffing Issues Slowing Road Repair[2]

- West Virginia’s commissioner of highways tours 50 miles of roads in Marshall County[3]

- Miller Brings Out Platform—Hits School Politics and Condition of Roads in Talk at Armory[4]

- Bad Road Conditions Trigger ‘Blockade’[5]

- Gov. Justice announces plans to fix secondary roads and refocus Division of Highways as maintenance-first agency[6]

These are all headlines from sources in West Virginia or Ohio. These headlines cover a broad swath of history, from 1936 to 2019, but all deal with the same pressing concern: the roads of West Virginia. West Virginia roads are, generally, very bad. The condition of the roads is a leading topic of conversation, in homes and businesses and schools as well as a leading talking point for politicians at all levels of government. Why are West Virginia roads so consistently an issue? Why are we having the same issues in 2019 as in 1974, 1936, or 1952? And why do we continue having these issues?

Topographical challenges

Transportation in West Virginia has never been easy. The land that would become West Virginia was wilderness. Ancient forests covered the hills, flowing down to narrow valleys through which pristine streams rambled. The forests were thick, with layers of shrubs and trees, and passage through them was difficult. The settlers who made it over the highest mountains, what is now referred to as the Allegheny Highlands, were indescribably brave, and tough. Today, we take it for granted that settlers moved to West Virginia and that our ancestors successfully ended up here. But imagine being part of a family two hundred years ago—often already having braved a transatlantic voyage, now slowly fighting through brush, your livestock laboring up the steep hillsides, days or even weeks away from the nearest community and help. Few of us have ever experienced this true isolation, where you are completely at the mercy of the environment around you, depending only on the strength of your spirit, your body, and your mind to get you through.

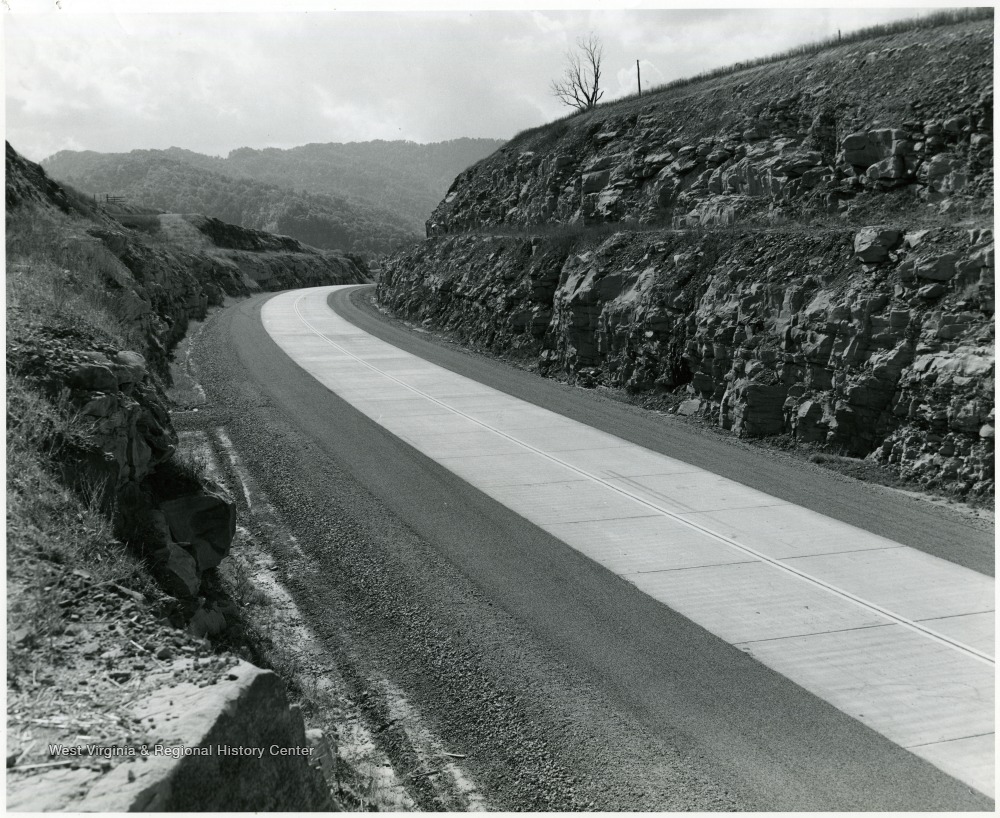

Eventually, the narrow paths through the forests turned into roads. The roads turned into highways. Rail lines moved in, and as the coal deposits opened up the furthest reaches of the state to the outside world, transportation became more of a priority. It wasn’t just coal that required a transportation infrastructure. Glass factories in the central and north-central part of the state, the steel mills of the Northern Panhandle, and later the chemical plants of the Ohio Valley all depended on reliable roads and rail lines to transport goods and services out of the interior of the state. Beyond the needs of industry, the citizens of West Virginia also needed good roads. For most of the state’s history, more West Virginians were employed as farmers than any other profession and having good roads to transport crops and livestock to markets was necessary. To this day, more people live in rural communities than anywhere else in West Virginia. Having dependable access to towns and cities for shopping, jobs, recreation, church, and healthcare is still critical. This much has not changed. And, sadly, neither has the main issues with our road infrastructure.

Inadequate Taxes

To discuss the problem of West Virginia roads, we first need to examine a major driving force in state history: absentee land ownership and its effect on tax revenue. “Absentee land ownership” refers to the ownership of land by individuals and businesses outside of state borders. In West Virginia, absentee land ownership goes back to colonial speculation, and as far back as 1800 only a handful of speculators owned 93% of all land in what would become West Virginia. The deeds for these vast tracts of land were often difficult to find and track, which meant that it was difficult for settlers to prove they actually owned the land they were settling on, which in turn set the stage for the mass eviction of West Virginia farmers by coal, rail, and timber companies from their land at the end of the 19th century. West Virginia politicians, especially at the state level, tended to have close relationship with absentee owners and corporations, and made sure that tax laws favored them, causing an enormous source of tax revenue to be lost. Early attempts to achieve severance taxes on national resources failed, as the power and money of the absentee land owners made sure that politicians would not support such a thing.

The problems of West Virginia roads became apparent as early as the 1920s. While the roads had never been great, by the 1920s they were beginning to severely lag behind the rest of the country. At that point, there were no major roads connecting large towns and cities. Farm-to-market roads[7] were unpaved, and creek-and-hollow roads were often merely trails that were impassable in bad weather. In some places in winter, like along the Little Kanawha River in Braxton County, it was easiest to travel along the frozen waterways to town than it was to attempt passage of the mountain paths. A “Good Roads Movement” was launched in order to improve the state of West Virginia roadways, with the goal of opening up the state to automobile traffic. However, the funding for the roads was not readily available. The coal industry reached its all-time high in the mid-1920s, and the state had failed to take advantage of its peak years. As previously discussed, it had not levied appropriate taxes against the coal operators. Instead, road bonds were passed by state voters to provide the needed funds to begin improvements to upgrade West Virginia roads to the standard necessary for automobiles..

Federal Interventions

The Great Depression also provided an improvement in the roads. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was established in order to employ out-of-work Americans in public works projects. In West Virginia, one of their biggest projects was in road construction. Farm-to-market roads were enlarged to 22 feet and built up with layers of rock and shale. Creek-and-hollow roads were expanded to 9 feet wide with the goal of providing passage in all seasons.

WPA improvements could only go so far. The farm-to-market roads were supposed to be finished with a permanent surface by the State Road Commission. However, massive tax law changes in the midst of the Depression gutted state revenues. An amendment was written into the constitution in 1932 which placed caps on property taxes, which initially seemed like a welcome relief for citizens during the Depression—and was certainly a boon to absentee land owners. However, county and local governments had long depended on property taxes to improve roads in their areas. With a massive decrease in these funds, local governments were forced to shift the burden of these improvements to the state government in Charleston. The state government suddenly found itself responsible for the upkeep and improvement of most of the state’s roads. Sales and gasoline taxes were adjusted to close the rapidly enlarging road fund deficit, which meant that the tax burden then fell on West Virginia consumers. West Virginia consumers were usually West Virginia citizens, who tended to have less income than their counterparts around the country. The absentee land owners, living out of state, were thus not affected by the sales tax changes—they won a decrease in property taxes and did not have to endure the trials that resulted. By 1937 the road funds that had been raised by bonds were spent, and there was no tax revenue left to make up for it. The roads began to crumble, only a few years after they were improved.

Postwar Promises

The postwar period was very difficult for West Virginia’s economy, and by extension its roads. West Virginia’s coal industry hit the beginning of the long decline from which it has never recovered. The Okey Patteson administration placed infrastructure improvements near the top of its agenda, but the funds were simply not there, and again a road bond had to be passed by state voters to perform the most basic of improvements. A $50 million bond was passed by voters in 1948. Additional bonds were passed to help fund the West Virginia Turnpike, which was opened in 1954.

The Turnpike was outdated as soon as it was finished. Originally planned as a four-lane highway connecting West Virginia on a path from the East Coast to the Great Lakes, instead it became a rough ride of only 2 lanes built using outdated construction technology. It cost three times what it was budgeted for. At the same time, the 1948 bond was only enough to pave, repair, and maintain existing roads and could not expand roads to the level needed for West Virginia to have a thriving economy. The Interstate Highways Act of 1956 promised funds to construct modern highways linking West Virginia to the outside world, but required 10% matching funds from the state, which of course it didn’t have. Construction was delayed for 2 years because of this, as well as the lack of state officials who could properly plan for construction. Additionally, the state was only allotted funds for 41,000 miles of interstate roads. It used most of the funds on the construction of I77, I64, I81, and I70. Other main thoroughfares like US 19 were left without vital upgrades, and much of the interior of the state was left without modern interstate roads.

The road condition would likely have continued to deteriorate, and at best stayed hopelessly out of pace with the demands of the postwar economy, had it not been for the national lens focused on West Virginia with the 1960 election. The spotlight on the state on John F. Kennedy’s campaign trail turned into a genuine commitment to improve the problems of West Virginia with federal assistance. After his assassination, President Johnson continued with the War on Poverty initiatives. These, among other things, resulted in the creation of the Appalachian Regional Commission. The ARC pumped funds into the state, overall bringing in 2300 miles of needed roads to the state and more than $93 million in road funds. At the same time, Senator Robert C. Byrd’s star was rising in the U.S. Congress, and his role on the Senate Appropriations Committee was vital for bringing in federal funds for West Virginia, much of went towards roads.

Roads Today

Throughout all of this, the fundamental issues with funding for our roads was never addressed. West Virginia never addressed the deep issues with its tax base, especially with respect to absentee landowners and the lack of appropriate severance taxes. Major improvements to the state’s infrastructure have consistently required bonds passed by voters or injections of federal and regional funds. During Byrd’s time as chairman of the Appropriations Committee, it was easy for the state to take infrastructure funds for granted. When he died in 2010, at the very beginning of the current coal bust, the state was again unprepared. Coal was not appropriately taxed during the preceding boom, and the state had been steadily losing population and thus critically-important taxpayers. Given the state’s consistent history of infrastructure issues, the state legislature at that point in time should have been foreseen the predicament in which we find ourselves today: with roads that tear up our cars, bridges that are becoming unsafe, and no money to do anything about it.

Sources:

Appalachian

Reawakening: West Virginia and the Perils of the New Machine Age, 1945-1972

and An Appalachian New Deal: West

Virginia in the Great Depression by Jerry Bruce Thomas.

[1] https://www.wboy.com/news/harrison/harrison-county-mayors-discuss-fixing-west-virginia-roads/1951508090

[2] https://www.wvpublic.org/post/west-virginia-officials-staffing-issues-slowing-road-repair

[3] https://wtov9.com/news/local/west-virginias-commissioner-of-highways-tours-50-miles-of-roads-in-marshall-county

[4] Charleston Daily Mail. April 11, 1936, page 8.

[5] Charleston Daily Mail. April 19, 1974, page 10.

[6] https://governor.wv.gov/News/press-releases/2019/Pages/Gov.-Justice-announces-plans-to-fix-secondary-roads-and-refocus-Division-of-Highways-as-maintenance-first-agency.aspx

[7] Farm-to-market roads were roads, that, as their name implies, provided passage for farmers from their homes to local markets. Creek-and-hollow roads were the winding roads that led further back in to the hollows, usually following winding creeks as they went.

Another great article!!