What is Polio?

The oldest documentation of polio dates back to the time of the ancient Egyptians. Carvings and paintings from that time period show adults and children walking with canes and visibly deformed legs. However, it wasn’t until the 19th century, as medicine was embracing scientific principles of diagnosis and description, that a standardized description and study of the disease was attempted. It is in this time period that we first see clear case reports describing the disease.

In most people, infection with a poliovirus causes minor flu-like symptoms. However, in about 1% of people the virus attacks the cells of the nervous system responsible for movement and eventually can cause paralysis. In severe cases, the virus attacks the nerves and muscles responsible for swallowing and breathing. These patients require significant assistance to do both, or they die. The older you are, the more likely you are to contract the paralytic form of the disease and the more likely you are to have severe symptoms. Children, for instance, rarely get this form and when they do it usually only paralyzes a leg. Adults who contract poliovirus are much more likely to develop severe paralysis of the breathing muscles.

Polio in Modern America

Until the 20th century, conventional medical wisdom held that polio was overwhelmingly a disease of poverty. It was also believed to be directly linked to cleanliness. Spreading by fecal-oral transmission, the belief was that careful attention to hygiene could prevent outbreaks. One of the quirks of American attitudes towards illness is that we tend to hold people personally responsible for their illnesses, and this was no different with respect to polio: if you or your children contracted it, likely you just weren’t clean enough.

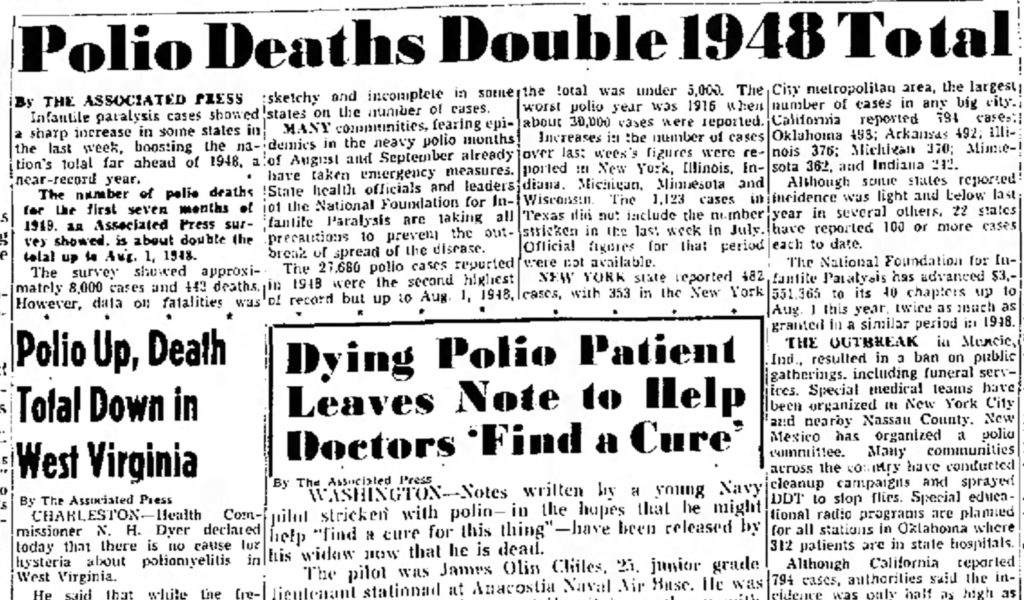

After World War II, however, a series of outbreaks rattled America. America was riding the postwar wave of prosperity. Science was advancing by leaps and bounds and the standard of living was higher than anywhere else in the world. The outbreaks, however, did not follow the conventional pathways. People of all ages, from all socioeconomic statuses, were infected. The children of poor Appalachians and of wealth suburbanites alike caught the terrible illness.

One of the disease’s most famous victims was President Franklin Roosevelt. During his lifetime he established the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (one of the names for polio at the time). Today we know it as the March of Dimes. While children were more likely to die of other diseases and accidents, the fundraising efforts of the Foundation brought enormous attention to the disease. Unfortunately, this had the side effect of creating near-hysteria about the disease. However, on the plus side, it directly contributed to the development of one of medicine’s biggest success stories: the Salk polio vaccine.

Vaccine Rollout in Appalachia

Millions of children around the country were receiving their polio vaccines, in the largest mass vaccination program in US history. The vaccine was slow to penetrate into the Appalachian interior. The reasons for this are numerous, as I discussed in my epidemics series. In brief, poverty, lack of infrastructure, and lack of healthcare personnel made it more difficult for Appalachian families to receive the medical care that was standard elsewhere.

The UMWA health program helped improve this situation, but it wasn’t enough. By 1965, only half of West Virginia’s children had been vaccinated against polio. This allowed a dangerous gap in herd immunity and the state remained vulnerable to the disease as a result. It wasn’t until the War on Poverty initiatives, which drastically expanded access to healthcare, that Appalachia began to catch up with the rest of the country. In the coalfields, the Appalachian Regional Commission was especially active in closing vaccination gaps. A contaminated batch in the early releases of the vaccine actually gave many children polio on the West Coast. However, with the assurance of public health officials in West Virginia, parents agreed to vaccines when they became available. Health officials held mass vaccination drives in the communities and at schools. Images in newspapers showed children lined up for their vaccines.

Today, rigorous school entrance requirements ensure that West Virginia’s children are some of the best-vaccinated in the country. This includes the polio vaccine, and the disease has been eradicated in this country. However, it is not eradicated worldwide. Many regions, whether because of anti-vaccine propaganda or infrastructure issues, continue to battle polio. Polio could always come roaring back if we became lax in our immunizations. Perhaps we would be able to prevent the worst of the disease outcomes. After all, we have 60 more years of medical advances behind us. Or, we could fail to recognize an outbreak in the early stages,. For most of us in the medical community it’s a disease of the past: something we learn about but never see in our careers.

What Can We Learn From Polio?

Over the course of a twenty-year period, from the late 1940s to the early 1970s, Americans faced a horrific disease. Polio attacked their children by the thousands. Like COVID, while most individuals who contracted it recovered well, a substantial percentage of victims did not. They died or developed permanent neurological damage. However, at no point in time did Americans consider their lives to be expendable. When you examine newspapers of the time, you don’t see the country shrugging its shoulders at polio. There aren’t people saying it’s only a bad disease if you’re poor or too old or too young. Americans were rightly horrified by it, funded the vaccine that helped eradicate it, and trusted the science that helped win the battle against. Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin became celebrities.

Comparing polio and COVID isn’t a true apples-to-apples comparison. However, I do find myself wondering how different things would be right now if the country approached COVID the way it had approached polio. Yes, there has been an incredible vaccine developed in record-breaking time. I certainly don’t want to discredit the work of the scientists responsible for that. Throughout this year I have remained consistently appalled at the people who shrug off COVID as just something that affects unhealthy people. Or old people. Or minorities, and go on living their lives without doing their part to help mitigate the spread. Even if this is true, and you’re more likely to die of COVID in these situations, what makes their lives expendable? What if we had decided in 1955 that polio was just a disease of poor children?

Excellent!!