“Lord willin’ and the creek1 don’t rise” was something I heard a lot growing up. It’s one of my favorite Appalachian sayings. It acknowledges that we can hope for the best but that even our best plans may be washed away. It embodies that particular Appalachian mindset that accepts the way things are, is deeply aware that ultimately so many things are beyond our control, but that we wake up always looking for a better tomorrow.

Of course, I never thought of it that way growing up. It was just a useful saying that everyone understood. It’s how we made plans, how we said goodbye, how we expressed fears and uncertainties.

“Mammaw, can I come stay the night with you this weekend?”

“Well, Lord willin’ and the creek don’t rise!”

“Mommy, can we go to the park tomorrow?”

“Lord willin’ and the creek don’t rise!”

“Do you think we’ll have the money to make it to town for groceries this week?”

“Well….lord willin’…and the creek don’t rise.”

A History of Floods

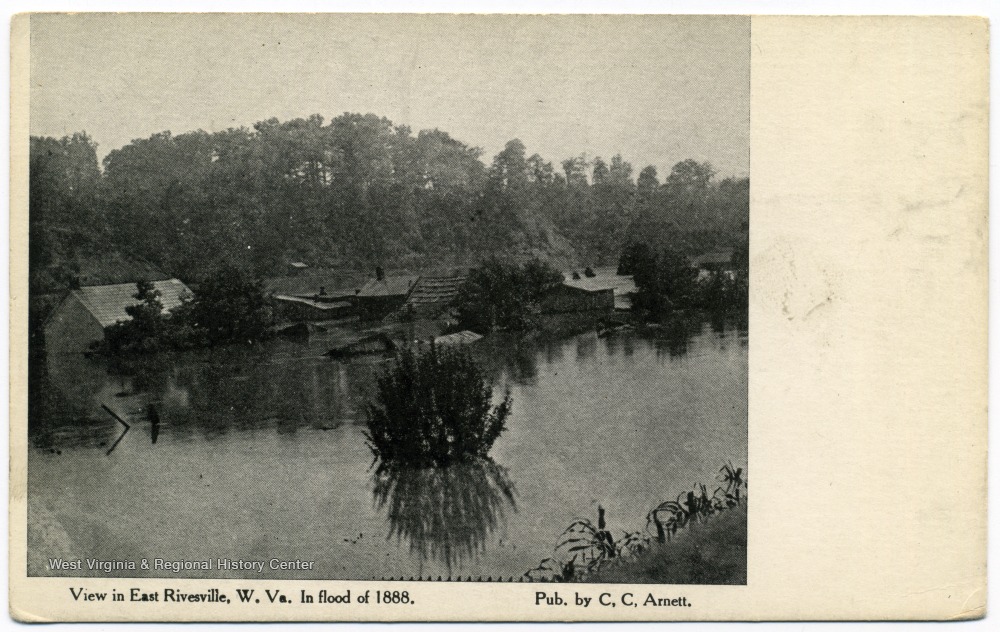

The reason this phrase is so common and ingrained in our culture is because the creeks do rise. They rise often and they rise high. The livable land here tends to be on the bottom lands near the streams and rivers because the hills and mountains are too steep and rocky. When those creeks and rivers rise they can destroy entire communities. Past floods live on in our cultural memory and the threat of future floods is always present. Everyone has a story about a flood–a flood they saw, a flood they helped clean up, a flood that hurt their family.

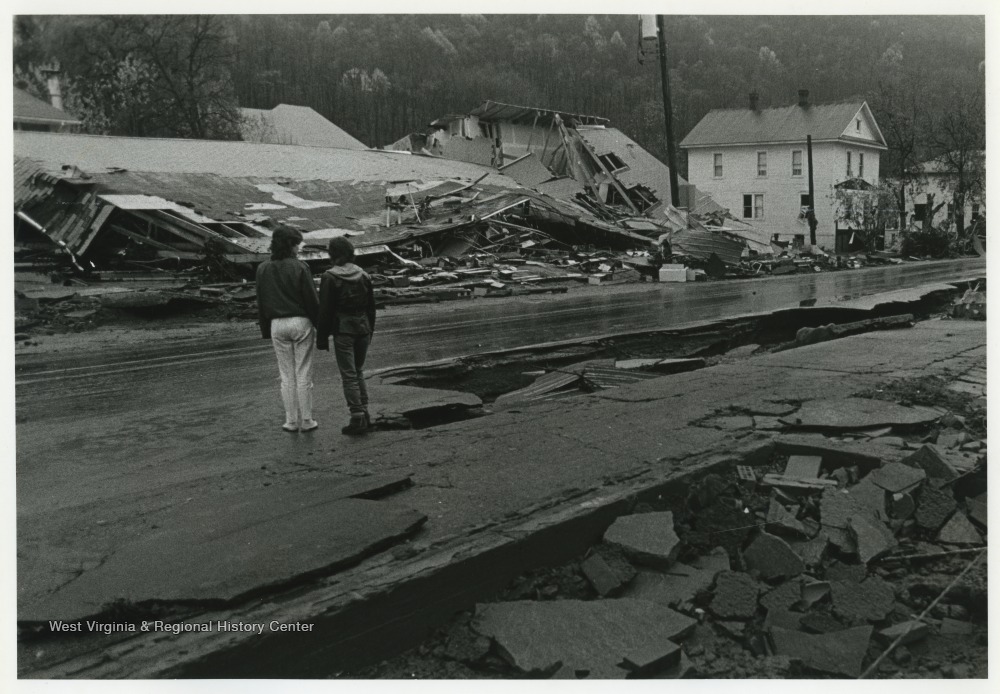

For me, the flood that hit closest to home was the ’85 Flood. The floods that year happened because of the same weather events that created the horrific flooding of Helene. A hurricane made landfall and a low pressure system connected with it, far away from the coast, dumped enormous amounts of water on the region. In West Virginia, the storm dumped 14 inches of water, smashing previous records. Along the Cheat River, the towns of Albright and Rowlesburg suffered devastating losses. The flooding destroyed 110 out of the 132 houses in Albright. 38 people died. I was born two years later and the memory of the flood in my childhood was still fresh. The US Army Corps of Engineers were constructing Stonewall Jackson Dam, and its lake, as a West Fork River flood control project. It was under construction in 1985, but it still saved my hometown of Weston from suffering a similar fate.

My dad was a veteran, and for the last several years of his US Army service he was in the West Virginia National Guard. The Guard often deployed him to flood relief around the state, usually to communities down in the coalfields. He was gone for weeks at a time, cleaning up flooded communities and repairing infrastructure. Throughout my childhood, the field across from my family’s trailer would flood with heavy rains. I have vivid memories from high school of driving through the more remote areas of Lewis County after a flood. I remember taking a day trip with my dad in college one time to drive along US Route 19 from Weston to Morgantown. We had to turn around in Rivesville because the road was flooded. In 2016 another terrible round of flooding hit the southern part of the state with water rising in minutes and wiping out important roads. In Elkview, the road to the main shopping area in town was completely washed out and 500 people were stranded there for more than 24 hours.

I also remember all the times our communities pulled together after a flood. Everyone checked on the elderly and the people who were in the more remote areas and had the hardest time getting around. Everyone made sure there was food and water. The citizens pulled together to donate and distribute critical resources and supplies. The floods may not get much attention outside of our region, and we may not get the relief from outside that we need, but we could start rebuilding ourselves.

A New Normal

I write all of this to illustrate that Appalachians are no strangers to floods. It’s one of the risks of living in this beautiful place. It’s in our dialect and deep in our cultural memory. It’s one of the many facets of our cultural kinship. It’s why I feel the tragedy in Western North Carolina and Tennessee as deeply as if it happened in my hometown. The homes, the communities, the people could be transposed into any part of Appalachia.

When I see reports of young families being washed away in the flood, I think of how I would protect my two little girls if a wall of mud came barreling down the mountain. When I read posts about missing grandparents and disabled veterans, I think of my own late father and how my family would have been able to care for him without electricity or water. I see homes that look like the homes of my childhood friends, trailers that looked like the one where I grew up, and country stores like the one we always ran to when we needed a gallon of milk or just needed to get out of the house for a bit.

With every new photo and story from the Southern Appalachia Mountains it is apparent that what happened to their mountain towns was worse and unlike anything else we’ve seen in Appalachia. We’re used to floods–this was different and there was no way to prepare for this. The death toll from Helene will far surpass the tragedy of the ’85 flood and the 2016 derecho. The topography will likely be changed forever. I’m scared for this new weather, that it won’t be too long before the same scenes will be coming out of West Virginia. In the meantime, I hope and I pray and I donate whatever I can and cherish my home. Will my children grow up visiting the same wonderful places I enjoy around the state? Will my part of the state be the next one that floods? Will my in-laws up Sandlick be safe in the next storm when they lose power? Lord willin’, and the creek don’t rise.

- Or “crick” depending on your particular Appalachian dialect ↩︎

As usual, another excellent article! Proud of You!!

As usual, another excellent article! Proud of You!