Individuals of all nationalities and ethnicities migrated to the Appalachian coalfields at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. Many of those groups are very familiar to today’s residents of Appalachia, for their descendants remain. Many communities in Appalachia, for instance, boast strong Italian American populations. The most beloved West Virginia treat, the pepperoni roll, came from these communities. As the coal industry entered its slow (and continued) decline after World War II, many of these groups moved elsewhere in search of new economic opportunities. As a result, we often forget how multicultural Appalachia has been throughout its history.

One such group that immigrated to Appalachia were Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe. Beginning in the 1880s, a large wave of Eastern European Jewish migration brought millions of Eastern Jews into the United States. While most settled in the large port cities of the East Coast such as Baltimore and New York City, many others spread out. By 1900, they had established thriving Jewish communities in the region. Many populations settled in the coalfields, but Jewish immigrants found new homes and successes throughout Appalachia.

Fleeing persecution and poverty

Jewish citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Russian Empire had hard lives. Technically, under Austro-Hungarian rule, official and institutionalized antisemitism was not permitted. Despite this, Jewish citizens remained the victim of significant discrimination at the hands of citizens. In the Russian empire, things were much worse, where antisemitism was an official governmental policy. The army conscripted Jewish men conscripted into the army where they suffered brutal treatment at the hand of officers and other enlisted men. Segregation laws kept Russian Jews confined to the Eastern part of the empire, the Pale of Settlement. They faced violent attacks and were only allowed to practice certain trades. The economic recessions that both Empires suffered further added to their troubles. For Jews in both empires, America offered an escape from oppression and new economic horizons.

Most Jewish immigrants had landed in America in New York City or Baltimore. There, they most often found work in the garment industry. Many of them had worked in similar jobs in Europe. They worked in factories, as tailors and seamstresses, or stores. Unfortunately, they found themselves facing a new kind of oppression. This time, it was at the hands of the American industrial capitalist machine of the Gilded Age. They struggled with low wages and poor working conditions and were often stuck living in cramped tenement buildings.

Some of the earliest arrivals, such as Jacob Epstein, opened up successful wholesale firms. Soon they were looking to expand their markets beyond the big cities. For the immigrants who were already weary of the industrial grind of the cities, this opened up a new opportunity. Peddlers began spreading out from the cities, bringing with them the goods of the big wholesale stores, offering them to rural families throughout the country.

New opportunities in Appalachia

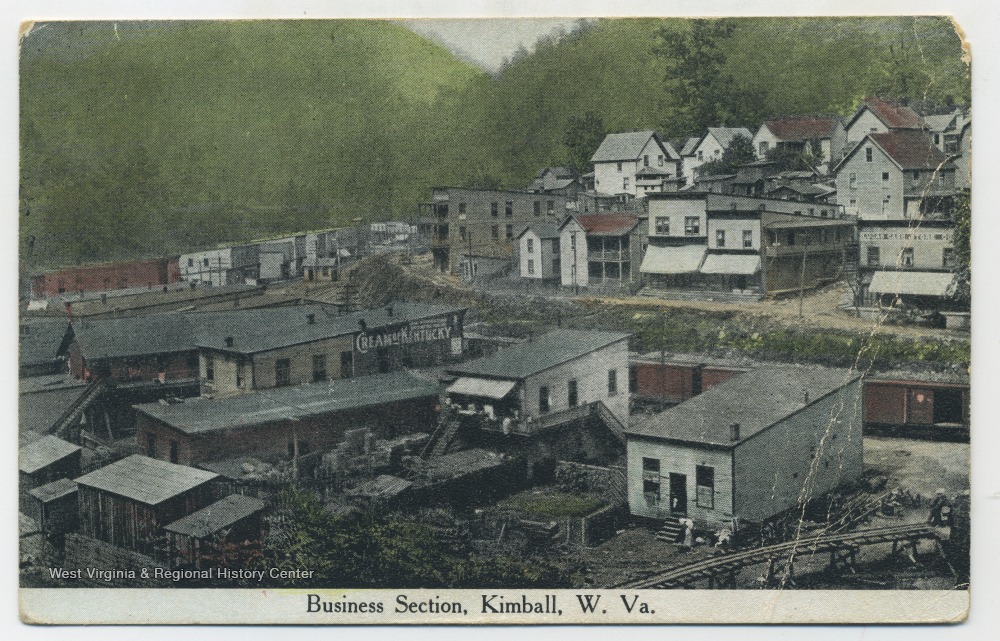

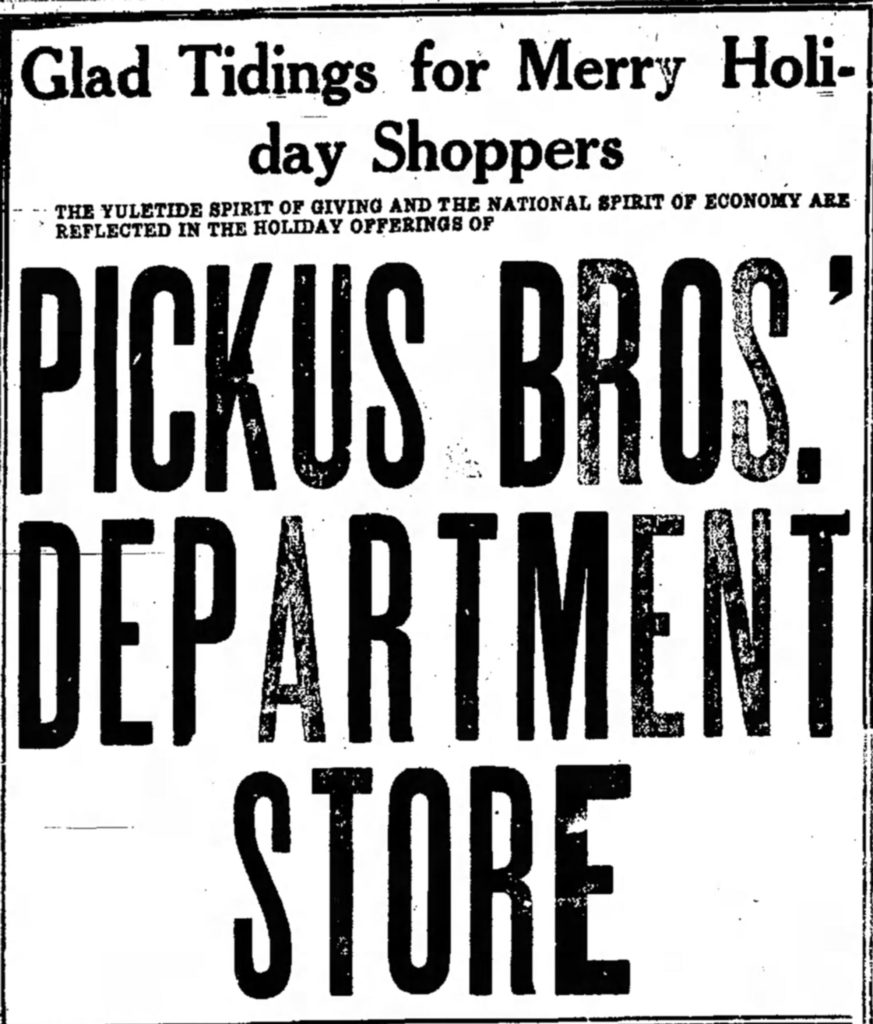

So it was that Jewish immigrants found themselves in the coalfields. First came the peddlers, following the railroad tracks to the coal camps. When the tracks ended, they climbed the hills, bringing the comforts of the retail industry to the families of Southern West Virginia. As time passed, they began opening stores. Jacob Berman opened a clothing store in Keystone. The Pickus brothers, Louis and Nathan, established successful large department stores in Beckley. As they became successful and established, their families followed. The rural communities of West Virginia resembled the villages they left in Europe. And, while the coal industry opened the region up geographically to them, their economic and social networks operated independently from the coal industry. This allowed them to interact with the industry in a way different than other West Virginians. The industry had not taken their lands or their livelihood and they were not forced into it. Instead, they were able to pursue economic opportunities on their own terms and were often successful.

By the 1910s, several communities in southern West Virginia had Jewish populations large enough to sustain synagogues. Keystone, Bluefield, Kimball, Welch, Williamson, Beckley, and Logan had regular sabbath services. Beckley, Bluefield, and Williamson still have their congregations, but the others have closed due to the dwindling population over the years. For the decades at the beginning of the West Virginia coal industry, Jewish immigrants had important economic and community roles. They found a life free from oppression and open with possibilities and enriched the coal towns in the process.

Further Reading:

Deborah Weiner has written extensively on the Jewish community in the Appalachian coalfields. In addition to her chapter in Transnational West Virginia: Ethnic Communities and Economic Change, 1840-1940, she published a monograph in 2006. Coalfield Jews: An Appalachian History is the only dedicated work on the topic of the coalfied’s Jewis past.