This post is picking up from part one. Please go back and read it if you haven’t already.

Things were not better at the end of World War II. Funding for schools, like funding for roads, remained a serious problem. West Virginia could not maintain competitive teacher salaries. Teachers began to leave the state in large numbers. Thousands left during the 1950s, many for Florida, where one school employed sixteen former West Virginian teachers. To make matters worse, West Virginia University conducted a statewide educational survey in 1957. The results were shocking. This Feaster Report revealed that West Virginia children trailed their peers in other states by as much as two full grades of education. However, West Virginia was unable to rectify the situation. Decades of a tax system that favored the rich and out-of-state interests left the state unable to fund its schools or appropriately pay its teachers.

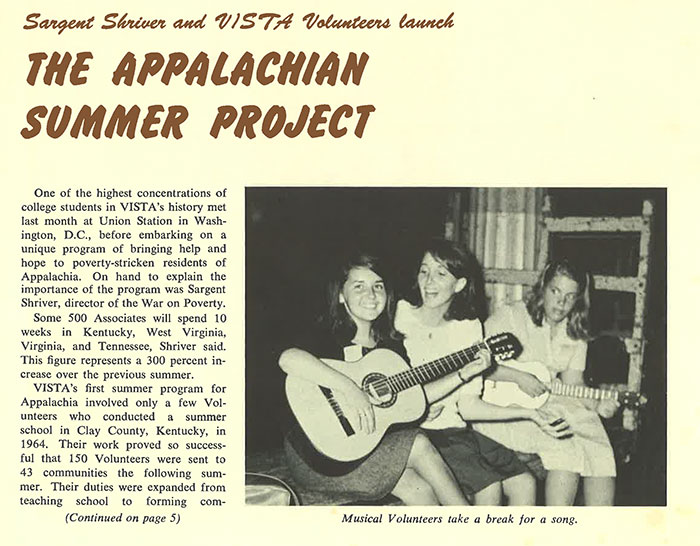

The schools, like the roads, benefited from the national spotlight brought by the 1960 Presidential Election. This spotlight highlighted the problems facing West Virginia, for better or worse. Kennedy’s social programs inspired many Americans to give back to their country. Domestic versions of Peace Corps-type programs formed, with the goal of putting young Americans into grassroots programs to fight poverty. Among these were the Volunteers in Service to America (VISTAs) and Appalachian Volunteers (AVs). The federal government, first under President Kennedy and then under President Johnson, enacted large-scale programs to improve the region. Money and volunteers were both pumped into Appalachia and West Virginia.

Schools did not receive the same amount of funding as the roads did, however. It was believed that the infrastructure, especially roads, was the most important thing to fix. The rural development theories of the time focused on shoring up “growth centers, which were areas believed to be most promising for future development. A focus was placed on improving the infrastructure of these areas. The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), formed in 1965 as part of President Johnson’s War on Poverty initiative, appropriated $123 million to West Virginia. $93 million of this went to the roads, and the remainder was split among schools and health institutions. This money was helpful, but it was not nearly enough to address all the problems of the public schools in West Virginia.

Citizen organizing played a large role in improving schools during the 1960s. The VISTAs and AVs wanted to empower West Virginians, especially working class ones, to advocate for change in their communities. The first of these groups, the AVs, embarked on a large-scale school repair project in Eastern Kentucky right across the border from West Virginia. It would continue to work on projects that improved the lives of school children in the West Virginia and Kentucky coal fields. VISTAs also coordinated many programs for the school children of West Virginia.

One of the most significant of the citizen action groups came out of War on Poverty policy. One of the features of this plan called for Community Action Associations (CAAs) to enable poor rural West Virginians to improve their communities. A very successful one of these was the Mingo County Equal Opportunity Commission. Ran by a high school history teacher named Huey Perry, branches of this CAA waged successful pupil strikes. These strikes resulted in the provision of free school lunches for poor public school children in the county. Perry threatened another strike if a local school wasn’t repaired. Despite the state government threatening him with arrest, his threat was successful and the necessary repairs quickly happened.

Unfortunately, this period of investment and action did not last. Local politicians were threatened by empowered citizens questioning the corrupted status quo. National-level politicians, among them Senator Robert C. Byrd, viewed groups such as CAAs and VISTAs as nothing but hotbeds of communism and sedition. The biggest blow came from the escalating costs of the Vietnam War. The money to improve the poorest areas of the nation was simply not there. By 1968 the War on Poverty was over, and with it the largest infusion of national attention and funding the region had seen.

West Virginia was lulled into a false sense of security in the 1970s as the coal industry experienced a brief boom. This boom was over by the early 1980s, and increased mechanization in the mines cost more miners their jobs. As they left the mines and then their homes, they took precious tax dollars with them. The state coffers, never prepared for bust cycles, suffered as well. The recession of the 1980s, combined with ARC budget cuts by the Reagan administration, further curtailed resources to maintain or improve schools. West Virginia lost $1.8 billion in federal aid between 1982 and 1986. Significant cuts were made to public school budgets. As with the roads, Byrd’s patronage injected needed funds into the state, but it was never enough to offset the inadequate tax base.

This story ends the same way it has ended for our roads. Here we are, in 2019, with a school system in desperate need of improvement and modernization, and no money to do it. Our state squandered the scant benefits of boom cycles and we are now unprepared for this long bust cycle, which is likely the end of the coal industry as we have known it. The problems with our schools go far beyond teacher seniority and the need for charter schools, as many politicians would have us believe. Our teachers can strike, but without a fundamental change in our state their efforts will continue to be frustrated—if not by politicians, then surely by the bleak realities of our state’s finances.

Good read…as usual…!!