West Virginia teachers have went on strike twice in the past two years. The strike of 2018 set off a wave of teacher protests around the country. The strike of 2019 was brief. The state legislature apparently learned its lesson: don’t threaten public education. Currently, the Senate is at it again. On June 3rd it passed yet another education bill, this time containing an amendment that prohibits teachers from striking. This legislation proposes sweeping changes to the public school system. West Virginia schools are dropping in quality and our students are not prepared for careers, goes the argument, and something radical must be done.

As with the issue of roads, the issue of the state of West Virginia’s public schools is not a new one. As with the issue of our roads, the problems facing our school have been the result of a long-term insufficiency of state tax revenues. Good roads and public schools are two of the most important services that our state government provides. They are also the most difficult to fund and spark some of the most heated debates.

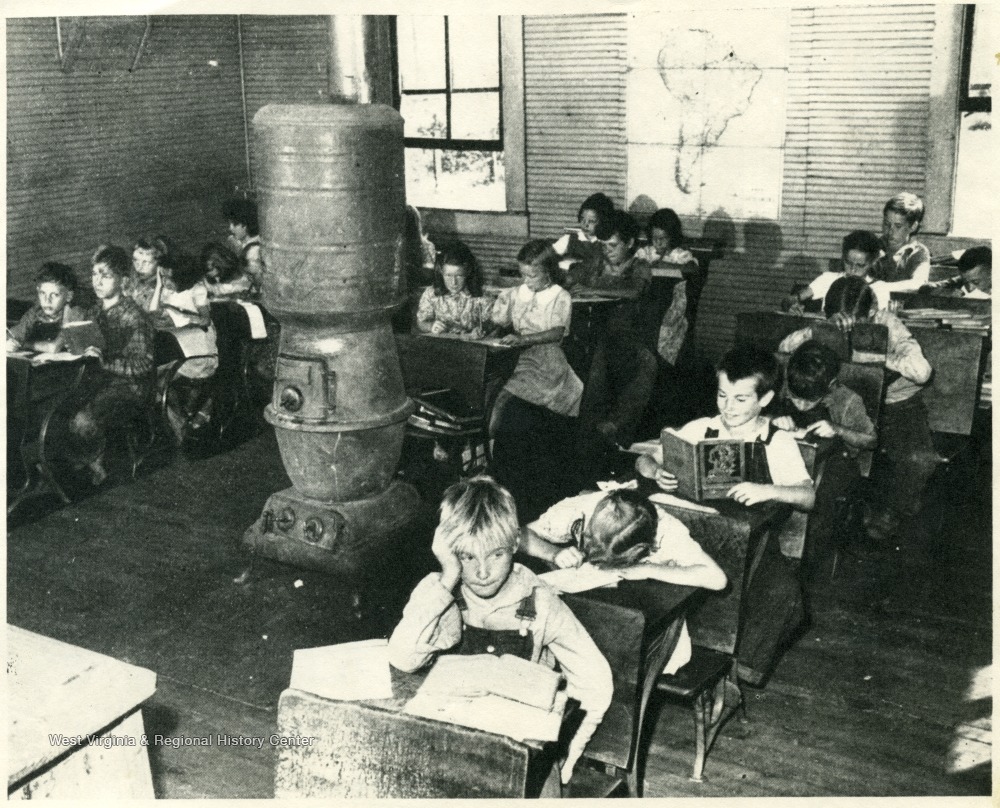

On the eve of the Great Depression, there was a public school system in place in West Virginia. This was the public school system of one-room schools, within easy walking distance for pupils, deep in hollows and high upon ridges. There weren’t good roads to transport students from isolated homesteads to larger schools in a more centralized location. As a result, the school system was decentralized, with numerous local school boards and districts. This infrastructure problem led to a patchwork of districts and school boards. The control of the schools and their funding overwhelmingly came from these local boards and local funding. There was practically no statewide or even county-wide standardization in curriculum or spending per pupil.

The Tax Limitation Amendment fundamentally changed the organization of the West Virginia school system. As mentioned in my last post, the Amendment gutted local tax revenues. Already experiencing losses because of the Great Depression, schools were in serious jeopardy. The solution was to establish the county-unit system. Instead of 398 districts and school boards, there would only be 55 school boards. Each county would have a single school board, which would report to Charleston. The State Department of Education would ensure consistency of curriculum and spending. The hope was that this would achieve three aims. The first was to shore up funding for public schools by pooling revenues in Charleston. The second was simplify the educational bureaucracy and decrease costs. The third was to improve efficiency in the state’s school system by instituting this centralized, uniform structure.

The county-unit plan was immensely unpopular with teachers. It was this proposal that saw the first big teacher demonstration in West Virginia history. Their main concern was that the plan was a kneejerk reaction to the problems of the Tax Limitation Amendment and that it was not properly planned or developed. The West Virginia Education Association had, in fact, been advocating for this scheme for more than a decade out of a desire to standardize and improve education in the state. It was not opposed to the principles but rather the execution of the plan. Regardless, teachers and administrators from all over West Virginia converged on Charleston as the the state government debated the county-unit legislation the Capitol. They swarmed their elected leaders and cheered opponents of the bill from the galleries. Their actions prompted then-Governor Kump to remark that, compared to the gas and coal lobbies, the school lobby was “the most disappointing, most unyielding, most unfriendly of them all.” Despite their efforts, the legislation was passed in May of 1933.

The county-unit plan was successful in cutting some administrative costs. These savings were not enough to offset the damage caused by the Tax Amendment. Throughout the rest of the Great Depression, West Virginia schools suffered from a serious deficiency of funding. Standards fell, low teacher salaries were cut even further, building maintenance funds vanished, and schools could barely maintain a nine-month term. This state of affairs would not change any time soon. In the next post, we will explore how West Virginia schools fared in the years after World War II and during the War on Poverty. The fundamental issues with the state’s tax system would endure, and the schools would continue to face difficulties.

Source: Jerry Bruce Thomas. An Appalachian New Deal: West Virginia in the Great Depression.

Keep them coming!!!

Glad you’re enjoying them!