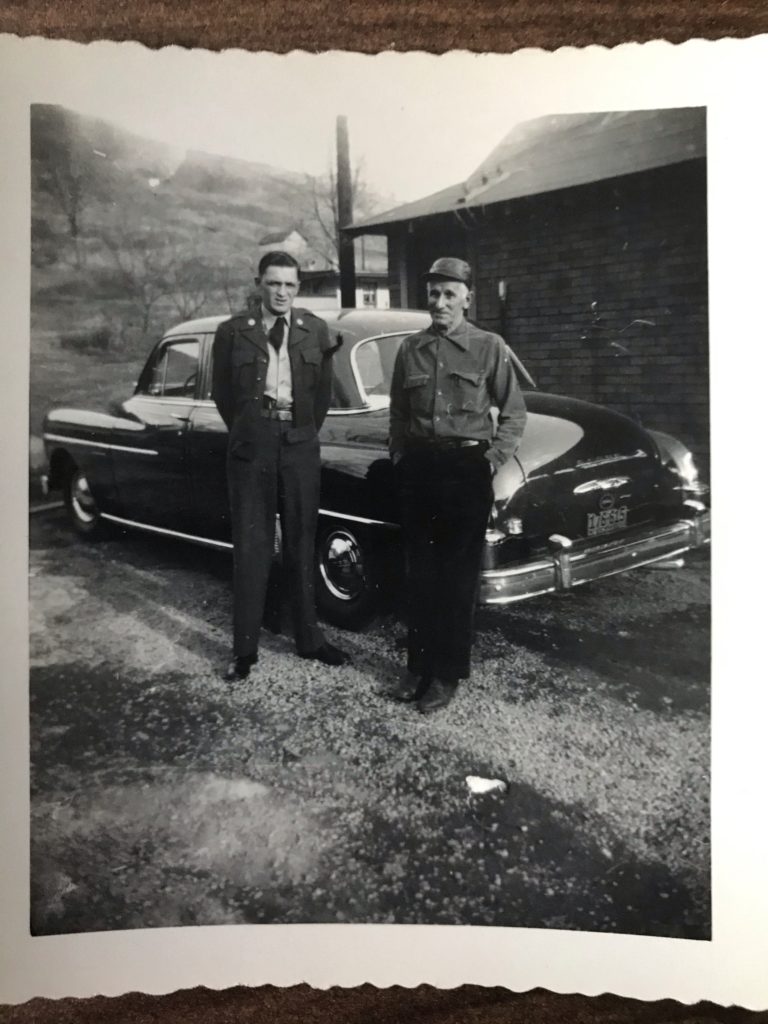

I love going to yard sales, flea markets, and antique malls. Of course, as a historian I am always on the lookout for an amazing they-didn’t-know-they-had-this, paradigm shifting find. Maybe some day I’ll find a box of important letters, or a diary like that of Martha Ballard. Most of the time, I don’t find much that interests me. Sometimes I will find interesting medical antiques, like old medicine boxes, or a pair of doctor’s saddle bags. Every one in a while I find something that touches me and makes me stop and think. A few months ago I was at an antique store here in Morgantown. It was their reopening day after moving to a new location and the store was absolutely packed (this was about three weeks before COVID hit). In a back room on the corner of a table against a wall I found a packet of about 40 military photographs, taken by an unknown soldier or soldiers. I love them. They date from the 1950s and cover a soldier’s life abroad in Korea and at home. At least one of the soldiers, perhaps the one responsible for the camera, was from West Virginia.

As a historian, when you use a primary source, you learn so much more from it than what’s on the surface. It’s not just about who is in the photograph or what the letter says. It’s about the other clues that lie beneath, and what the source’s existence can tell you about the time period. These photographs don’t just document what a soldier’s home looked like, or what the inside of his barracks looked like. It also tells us what things he found important enough to stop and document. What things he found fascinating, or moving, or fun. Things he would want to come home and look at some day, remembering the friends and experiences he had.

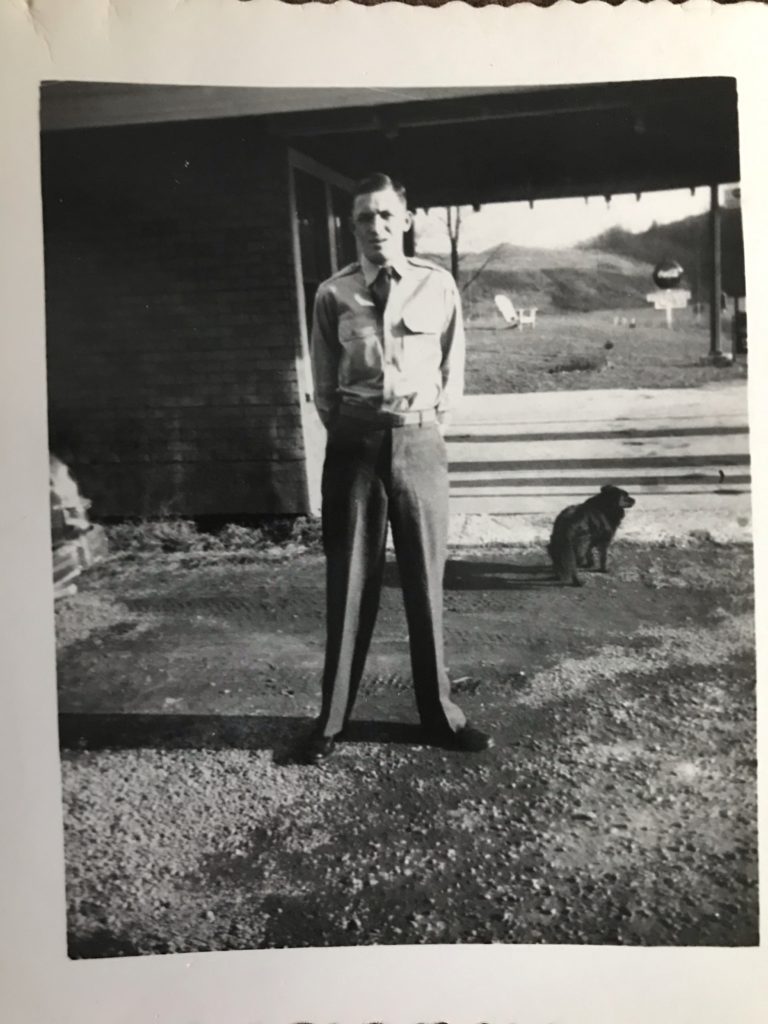

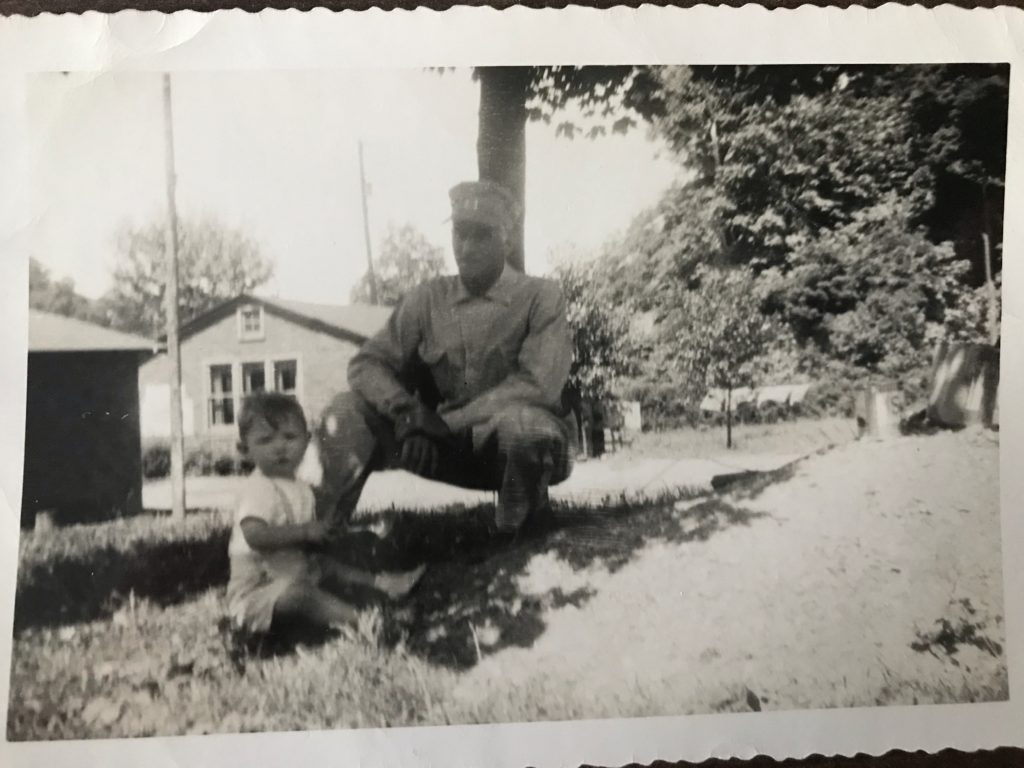

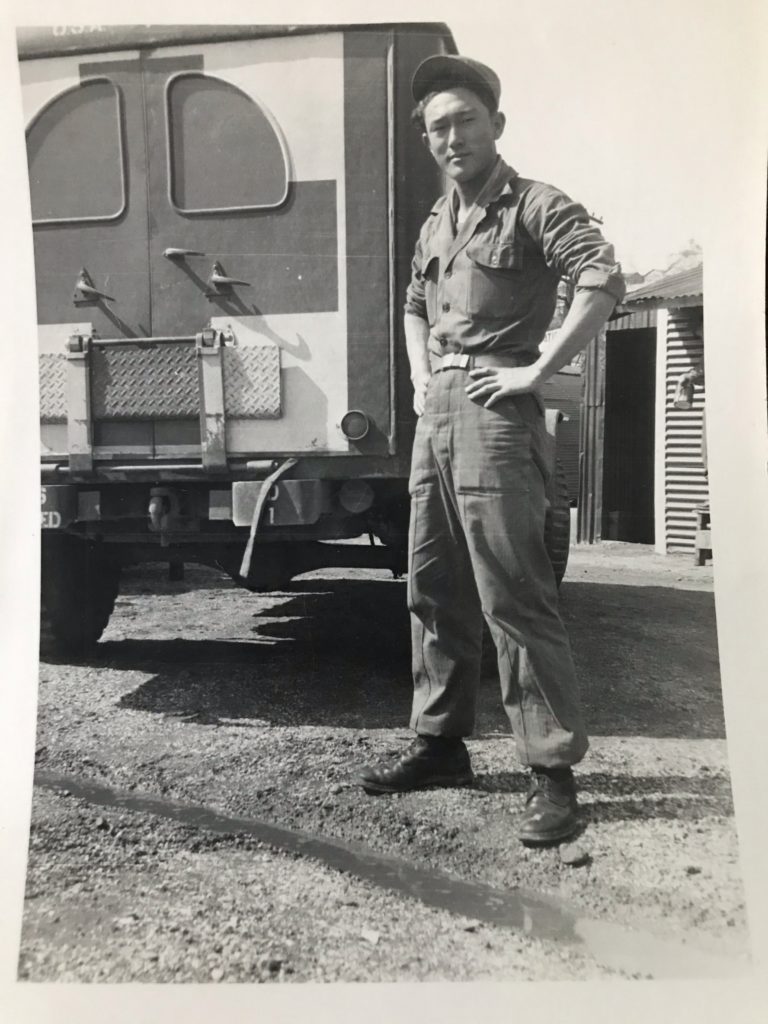

Some photos you can clearly imagine hanging at the soldiers bunk or kept in his wallet as he served thousands of miles away from his home and family.

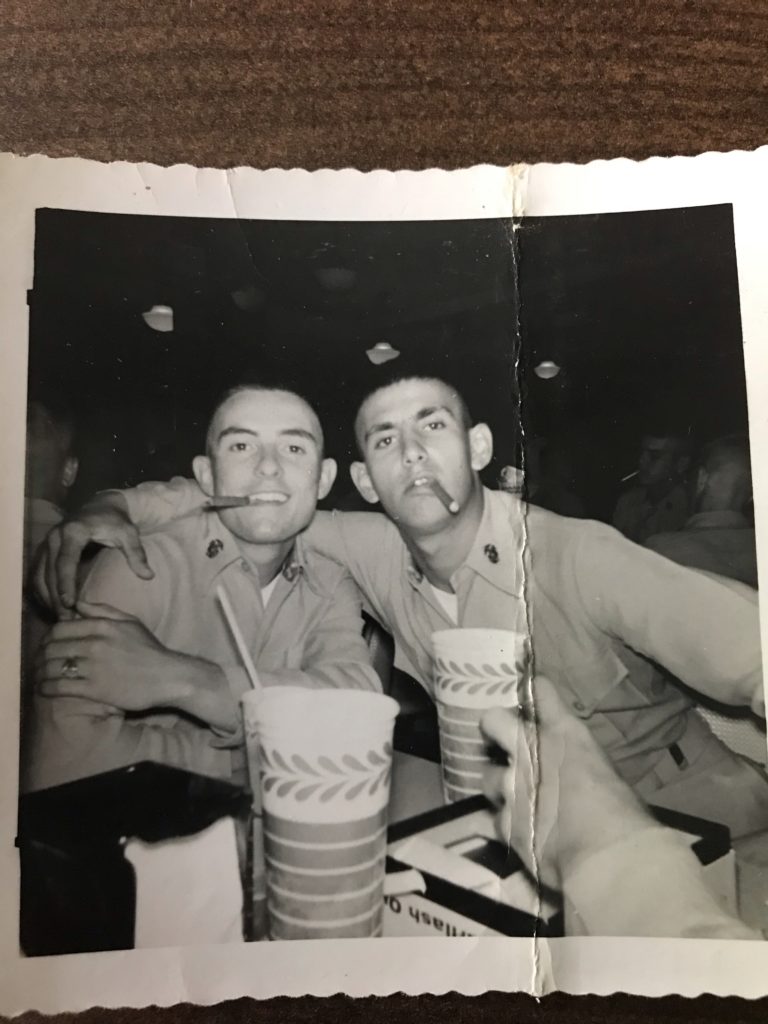

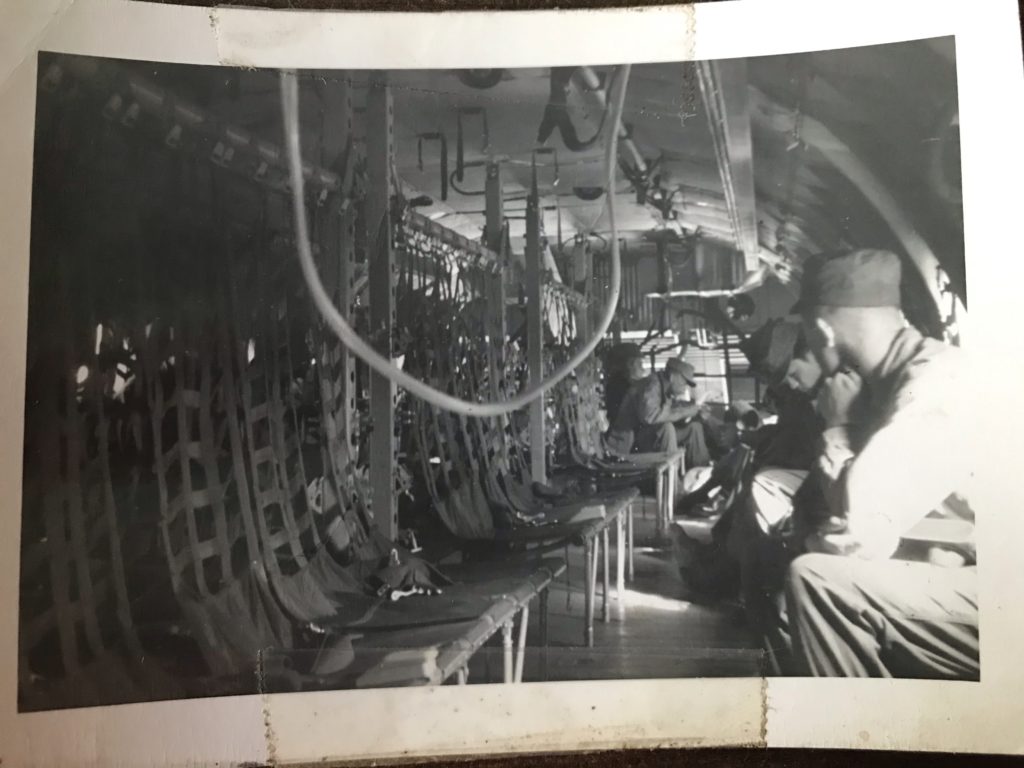

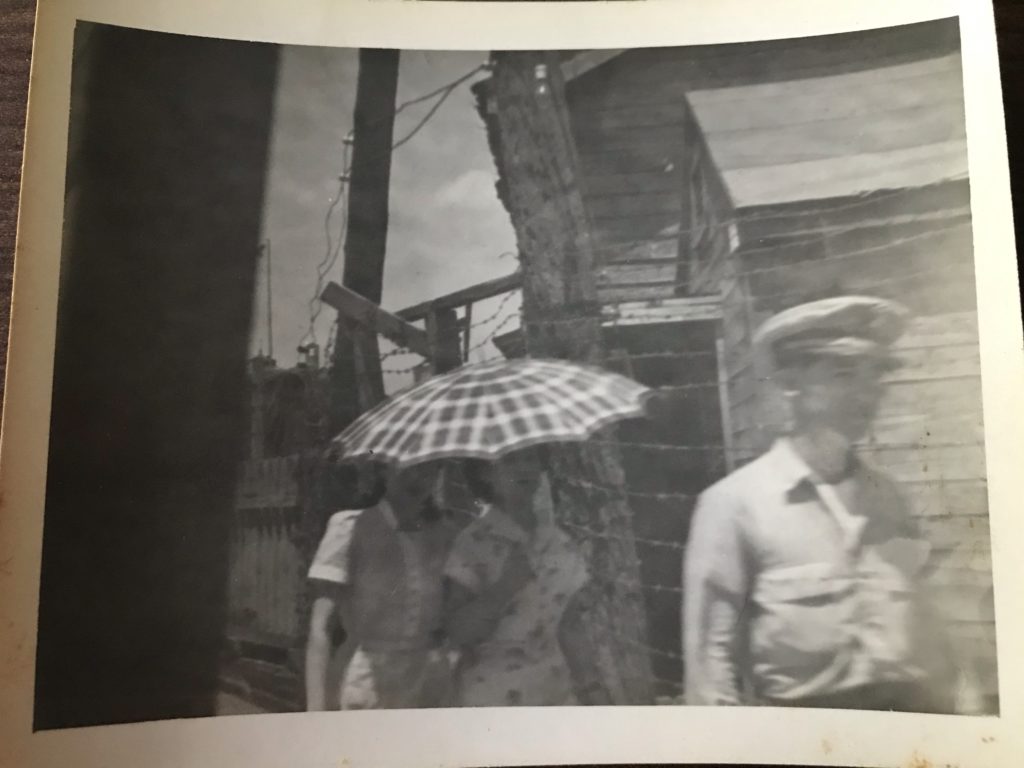

Other photographs are timeless and look as if they could have been taken by any young soldier today. They show real people enjoying life and friendship.

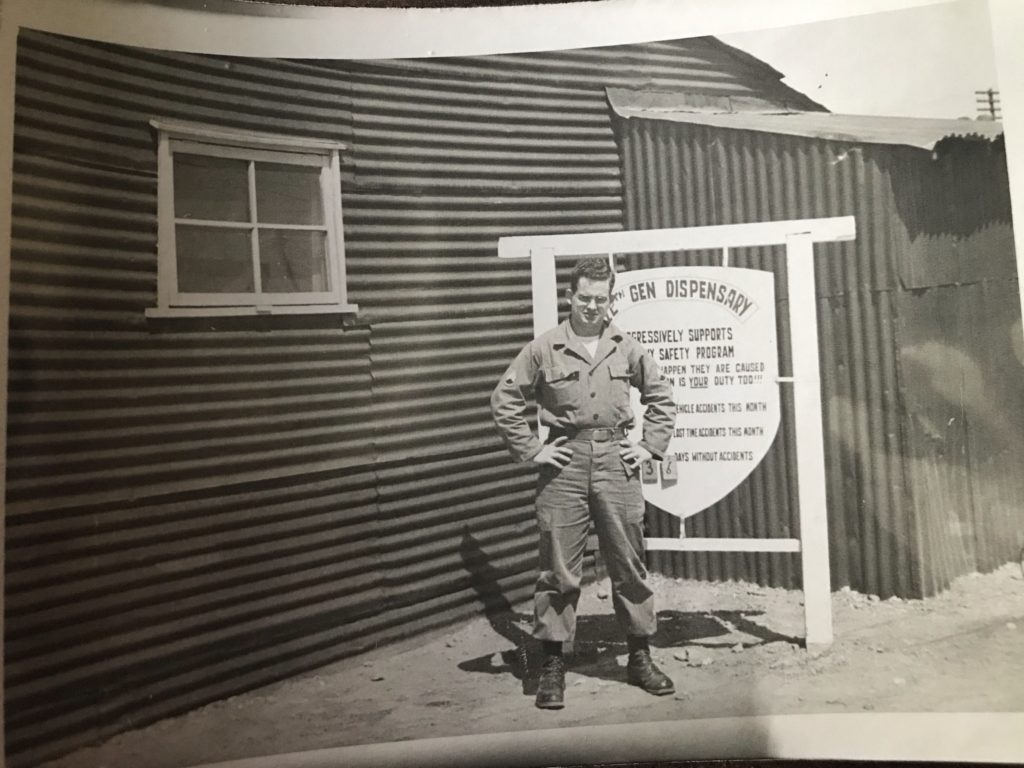

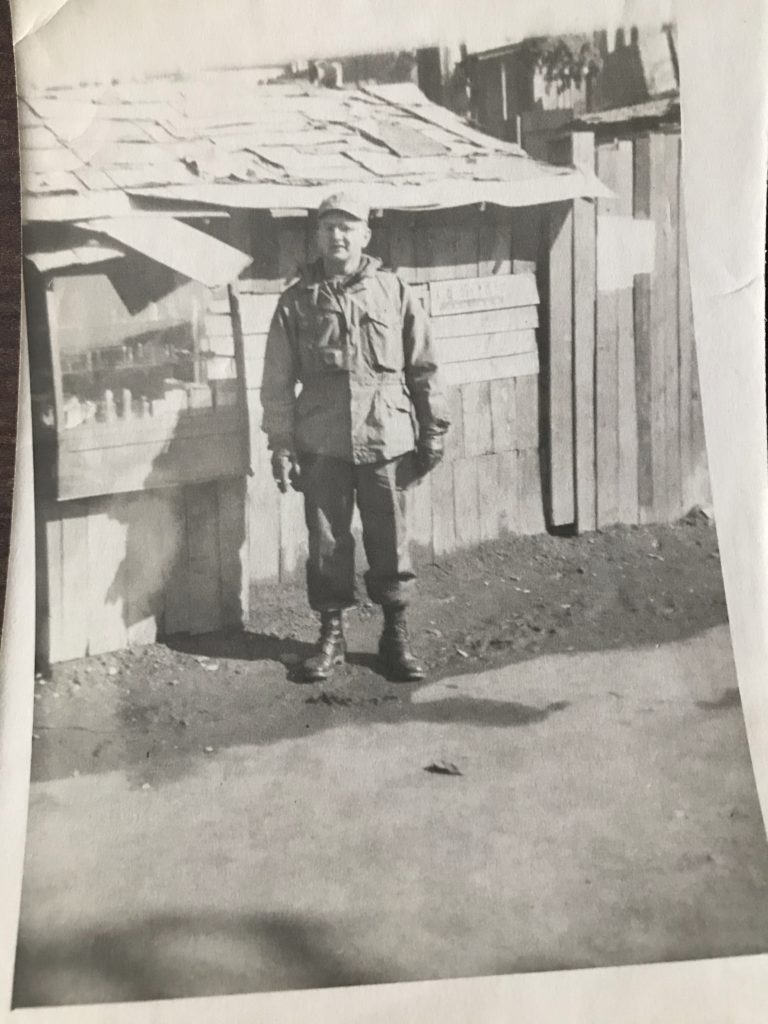

Some show the daily grind of the life of a soldier. I especially love the one immediately below, showing a medic outside the camp dispensary. 38 days since the last accident.

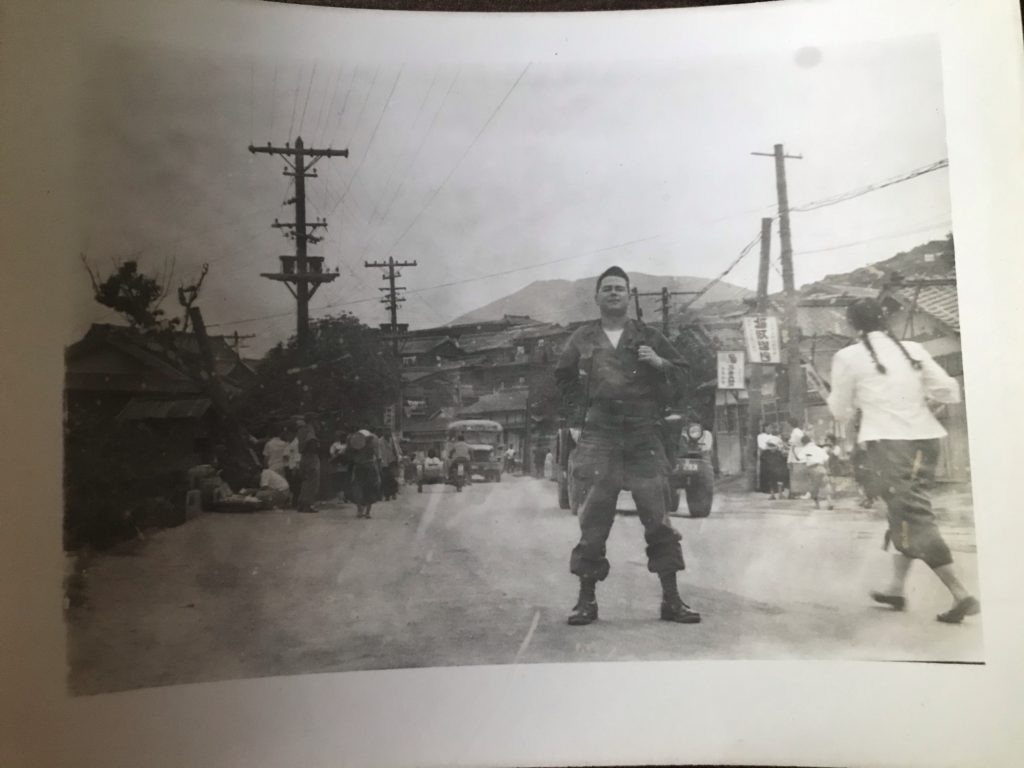

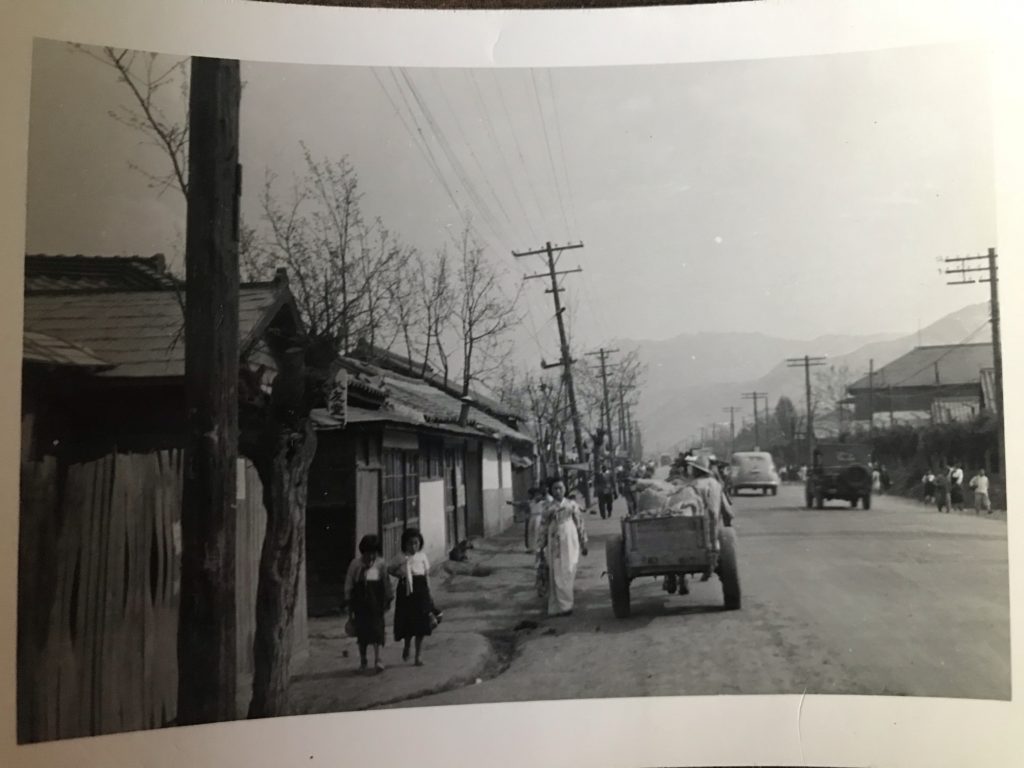

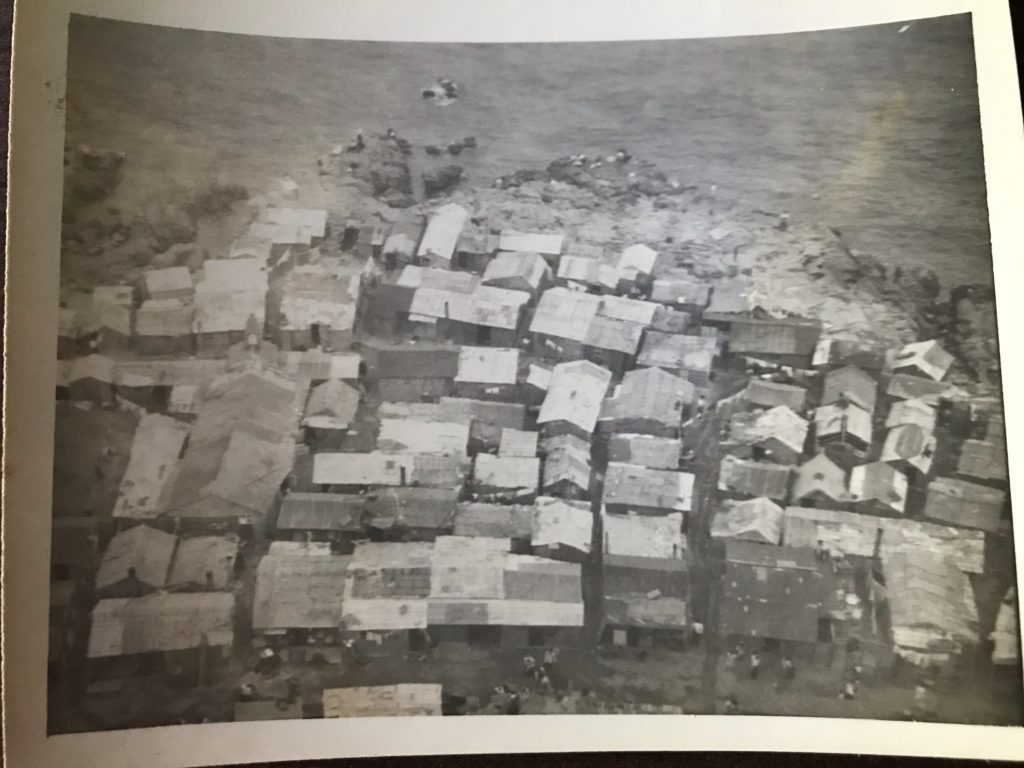

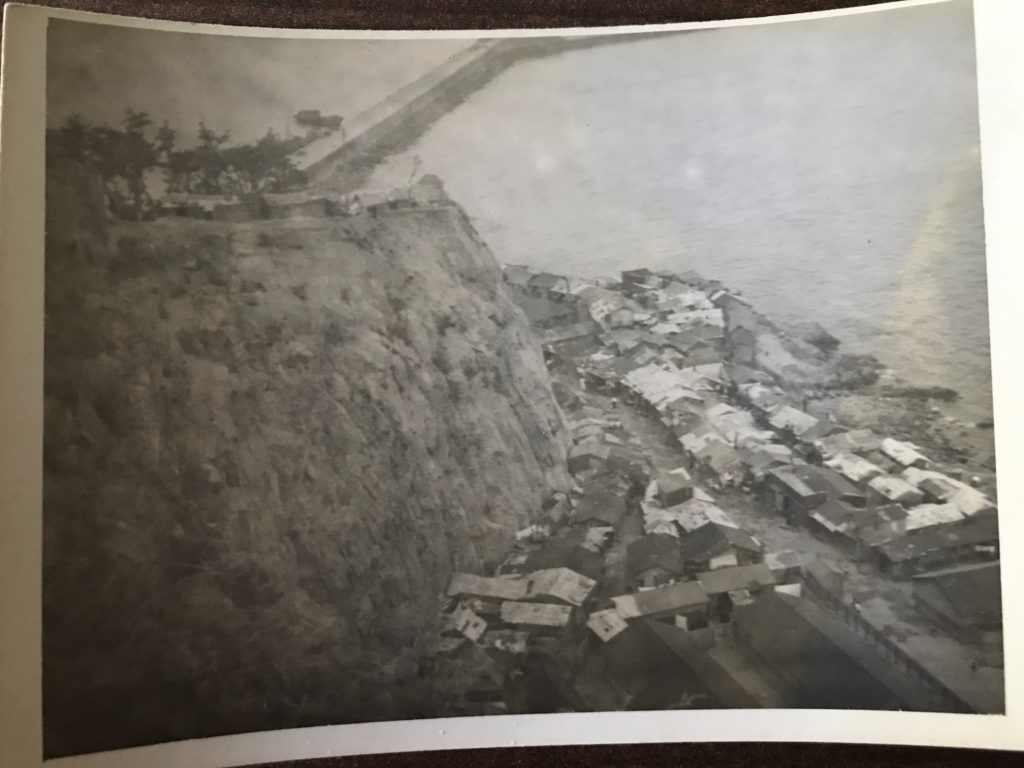

The other photographs are photographs that were clearly taken on deployment and show the streets of a Korea town and base. They capture that feeling you have when you first visit a country vastly different from your own. I remember my first trip abroad, to Guatemala. It was so different, not just from a language perspective but from every perspective. Different houses, different people, different snacks, different roads and infrastructure. Everything was worthy of a picture. I know exactly how this soldier felt when he took these pictures.

Several of the pictures show what appear to be local Koreans posing with their equipment. I believe he had formed friendships with them and wanted to document this.

1,354,664 deaths+. That’s how many Americans have died in the service of our country. We don’t have an exact count and believe it to be higher than that. I don’t know any of the men in these photographs, if they died in service, if they lost friends in service, or what they did when they came home. On Memorial Day, we need to remember the brave men and women who gave their lives for us. It doesn’t matter if you think the wars were just, it doesn’t matter what you think of the government or the armed forces as institutions. What matters is that these individuals made the ultimate sacrifice for others. They were people with families and homes and dogs and friends, they were young men wide-eyed at their first glimpse of a foreign country, boys smoking cigars and laughing. Let’s remember them today as people with full lives and histories as important as our own.